You say Teredo and I say Bankia …

… let’s call the whole thing “Shipworm”! Except, it isn’t a Worm, it’s a Clam.

We are all familiar with the abundance of “wormy wood” on our beaches. It makes lovely decorative lumber, but it is tricky to mill, because the boreholes tend to be filled with sand and pebbles. (A lovely project the author has seen was a ceiling made of thin boards, the many perforations of which allowed the light of concealed lamps to escape as through a constellation of stars.) The era of wooden ships has passed, and shipworms now only threaten wooden pilings and rafts, but they won’t easily live down their bad reputation…

Of interest to natural historians are shipworm-infested logs that only recently washed ashore. When those are sawed into, the actual inhabitants can be observed. This can be a messy business. A fully grown shipworm may be over a meter in length, and that represents a lot of soft and slimy tissue getting cut up.

What becomes immediately obvious is the fact that the tunnels are lined with white shell material, which sometimes can be separated in short intact sections, and this may be one of the features supporting the worm-association: worm, as in tube worm.

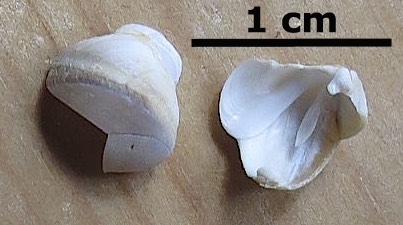

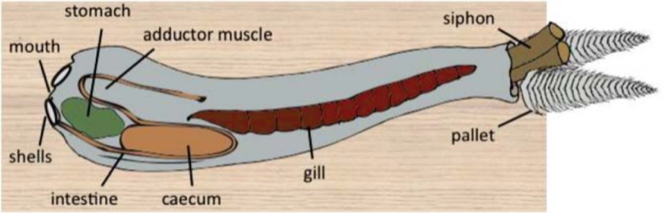

Closer inspection will reveal two shelly bits at the distal (innermost) end of a tunnel, which turn out to be the modified valves of a clam.

These shells have angular cut-outs and a raspy surface, and, by rocking left-right-left-right, the clam can slowly cut its way into a log, preferably parallel to the woodgrain.

Note how small the shells are in relation to the body size.

[divider_flat]

Note also the large size of the caecum, the organ responsible for breaking down wood cellulose with the symbiotic aid of bacteria.

(Perhaps not surprisingly, Beaver also have an exceptionally large caecum, and for the same reason: they too need the help of bacteria to get nutrition from cellulose.)

[divider_flat]

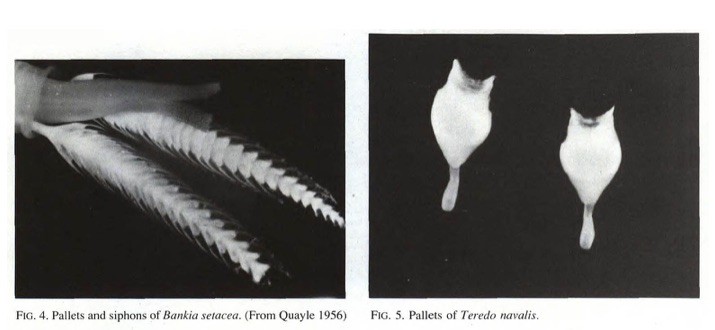

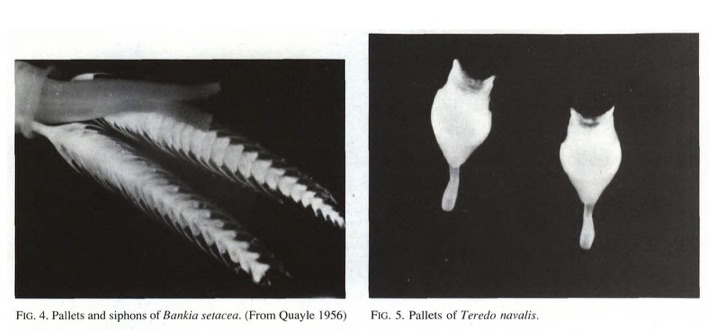

In order to breathe and to expel fecal matter, the shipworm has two siphons which exit the wood into open water. Close-by are two strange looking structures, called pallets. Their apparent purpose is to block the borehole against silting during storm events, retain moisture should the inhabited log go dry at low tide, or perhaps to defend against intruders.

These pallets are of specific importance to this report, since their architecture is what distinguishes Teredo from Bankia!

If the pallets have a “feather-like” shape, the shipworm in question is Bankia setacea.

If the pallets have a “feather-like” shape, the shipworm in question is Bankia setacea.

There is a good 1992 publication (pdf available on the Internet) by D. B. Quayle – a Fisheries and Oceans scientist, familiar to local shellfish farmers because of his publications on aquaculture. The above illustration is from page 3 of “Marine Wood Borers in British Columbia”.

One can hardly be mistaken for the other – but, even without comparing, it is a very safe bet that the ship-wormy wood you observe on local beaches has been colonized by Bankia.

Teredo navalis is a species indigenous to the Atlantic and, in BC, has only been reported from Pendrell Sound, East Redonda Island, where it is said to have established itself around 1960. Pendrell Sound is famous for the unusually high water temperatures that are attained there every summer. This fact is exploited by the oyster industry, who use a number of contraptions to collect oyster spawn on suitable surfaces for subsequent transport to other beaches or raft operations. It is tempting to speculate that Teredo was inadvertently brought to Pendrell Sound, arriving in wooden oyster seed crates from Japan. It is also possible that Teredo arrived the old-fashioned way: in the hulls of wooden yachts, coming north from the US: Teredo had been introduced into places like San Francisco and San Diego 100 years earlier (again, by way of wooden crates from Japan. How Teredo got to Japan is, obviously, another story…).

Apparently (and luckily) the waters around Cortes Island are not inviting to Teredo, or surely this exotic species would have spread beyond Pendrell Sound by now.

For the student interested in the variability and adaptability of living organisms, the shipworm is a fascinating subject. Here are bivalves, whose two valves have been reduced in size dramatically and whose function has been radically repurposed. The mantle’s ability to secrete shell material has been diverted to the lining the wood-tunnel walls, and two specialized and unique features, the pallets, have been invented. The latter deserve a lot more attention and investigation. Questions of homology need to be asked : are the pallets a modified element present in other bivalves ? And, especially in the case of Bankia, the intricate morphology of the pallets suggests functions beyond the mere closing of the tunnel.

Any reader who has reason to believe that Teredo navalis occurs in local waters other than those of Pendrell Sound is encouraged to contact the author of this blog at edgeswamp@gmail.com.

(All photographs are the author’s, unless indicated otherwise.)