Part Two

The year 2018 brought changes that had major impacts on the continuation of the Buchia story.

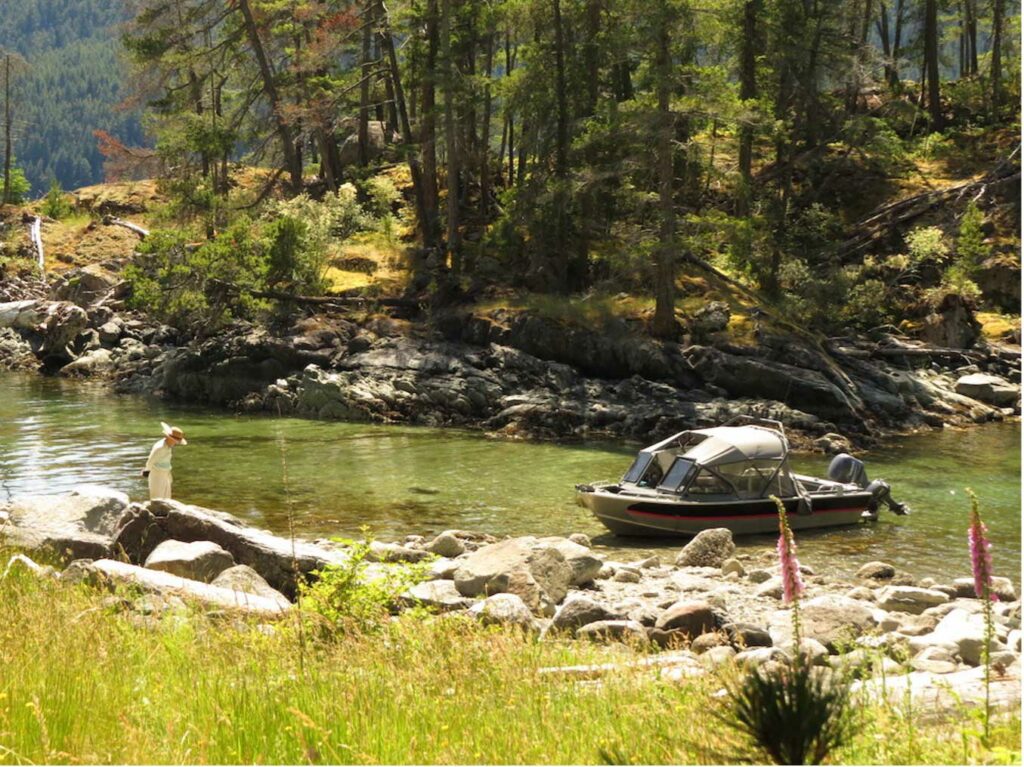

Aileen and I acquired a reasonably seaworthy boat, which extended the range of our investigations considerably. Team Buchia was now able to peer along the imaginary “magic line” and set out to follow it up north to wherever it would take them.

The year 2018 also brought The Healey Factor to bear on the Buchia scene. Jan, Carey, and daughter Hannah, friends and next-door neighbours took to the pursuit of fossiliferous erratics with unparalleled enthusiasm – and success!

Jan, Hannah & Carey Healey

“Happiness is finding a fossiliferous erratic on Discovery Island beaches!”

Two examples of the excellent specimens the Healeys contributed to the growing catalog of Buchia-erratics.

Our fossil count had gone beyond the 70-mark, yet none of those finds expanded the range of known Buchia occurrences or brought us any closer to determining where the source rocks of the erratics in question might be located. We had competing ideas and decided to explore the notion of the “magic line” by following it as far north as we could. The pleasant corollary to that approach was the likelihood of finding more Buchia specimens. We were not disappointed, as the following images prove.

A remarkable variety of preservation styles were encountered, we benefited greatly from local hospitality, input and contributions and returned home with a dozen more records. We also extended the range of known Buchia-erratic occurrences all the way to the southwest shores of West Thurlow Island.

We tried our luck up Phillips Arm, and we visited legendary Dane Campbell up Loughborough Inlet, but those locations did not yield any specimens. Talking to numerous locals had mixed results: Dane had never encountered any rocks like the Buchia samples we could show him. Jonah, the son of Blind Channel Resort proprietor Eliot Richter’s son Jonah and his wife Agnieszka were proud to show us their Buchia fossils, found right where they live. Shoal Bay’s Mark MacDonald had an interesting story about a fossil, which turned out to be a Late Cretaceous Inoceramus bivalve from Sucia Island in the San Juans…

The Lead Scientist (“Lead” as in Pb, as the rest of the team liked to refer to me) engaged in hard field work in Shoal Bay, inspecting Fossil #79 and sampling some of the local beer (Fig.36)…

The results of the Blind Channel Expedition were inconclusive, if not downright misleading. Loughborough Inlet and Phillips Arm had been disappointments – much like Bute Inlet had been eleven years ago.

Considering the directions of fjords, channels and passages, the movement of the last glacial advances can be reconstructed. Any material north of the Thurlow Islands would have been transported up Johnstone Strait – not down towards Cortes Island, where, in fact, much of the material in question had ended up. Having been frustrated in our attempts to demonstrate that the Buchia-erratics had been transported by glaciers down various Coast Mountain fjords, we had to consider the Thurlow Islands themselves as their source. The local geology does not support such a notion. TeamBuchia, originally preoccupied with the finding of fossils, started to think more and more like glaciologists – and we decided to devote our second Blind Channel Expedition to answering questions directly related to Ice Age glacial movements and ice-flow directions.

*********

In the meantime, closer to home Johanna Paradis, from Maurelle Island, and her sons Kay and Jack Sutherland reported on their fossil-finding successes and swelled the list by six specimens, collected over the span of several years. The most attractive piece is Fossil #85 found on the east side of Read Island (Fig.37).

The year 2020 began with a steady trickle of local Buchia finds. Sabina Leader Mense turned over a beach boulder as part of her regular foreshore monitoring program on Coulter Island and discovered that she was holding a Buchia-erratic. The piece (Fossil #92 Fig.38) demonstrates an obvious fact: there is probably a large number of specimens hidden by epifaunal growth, or simply by water depth, in the low intertidal zones.

Fossil #93 is also noteworthy, since it contains an obscure group of single-celled organisms, known as Agglutinating Foraminifera, identified by Jim Haggart as Bathysiphon sp.

The amoeboid organisms construct tubeworm-like shells from particles they select from the ocean floor. (Fig.39)

The second trip to Blind Channel was again very pleasant and even more successful than its predecessor in terms of numbers of Buchia specimens found, even though we deliberately spent a large amount of time exploring beaches that were not very promising. As mentioned earlier, Team Buchia was pursuing glaciological questions now, and we were looking for evidence to support or disprove a number of ideas we had. One was the possibility that glaciers coming down from the heights of Vancouver Island had transported the erratics of interest to where they could have been swept up by other ice flows and moved as far south as Cortes Island. We crossed Johnstone Strait a few times and combed numerous Vancouver Island beaches directly across from the Thurlow Islands, where we had found many Buchia-erratics before.

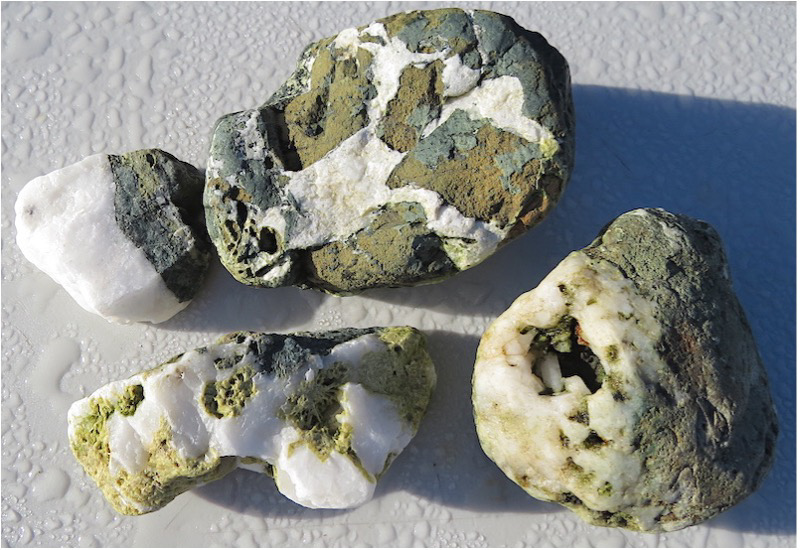

The first thing that struck us after landing was the conspicuous abundance of a certain type of rock (Fig.41).

Brecciated Karmutsen basalt, held together by white quartz, mixed with metamorphic minerals like epidote and chlorite.

Karmutsen basalt is the most common rock type on Vancouver Island, with spectacular occurrences of pillow lava (i.e. caused by underwater eruptions, as they occur around Hawaii frequently).

We have since learned that the brecciated version of this rock is known as “Dallasite” and that it is considered a gemstone of some value!

What makes this easily recognized rock of interest to our pursuit is the fact that we have not found it anywhere on the Thurlow Islands. This, together with the fact that no Buchias were found on the Vancouver Island beaches we inspected, suggests that no glaciers crossed Johnstone Strait to override the Thurlow Islands.The fossil specimens we collected during our second Blind Channel venture were mainly small cobbles like the ones in Fig.42. They extended the known range of Buchia occurrences slightly to include the northern shores of West Thurlow Island, but otherwise just filled in a few empty spaces and – not insignificantly – contributed to the team’s happiness…

It was time to double-check the northeastern limits of the Buchia range – in other words: time to challenge the notion of the “magic line.” We returned to the mouth of Phillips Arm (Fig.43) and took another, closer look.

Phillips Arm splits into the southwesterly and southeasterly reaches of Cordero Channel, with Shoal Bay at the northern tip of East Thurlow Island being the vertex.

Exploring the narrow rock fringes of the western branch, we were surprised and exhilarated to find fossils Fossils #108 to #113 (Figs.44 and 45).

Inconspicuous pieces, with Fossil #111 of additional interest, because it contains two belemnite casts (Fig.45).

This was tantalizing, if not quite convincing, evidence that Buchia-bearing erratics had travelled down Phillips Arm. Another piece in support of that notion was found on the opposite (eastern) shore, Fossil #114 (Fig.46).

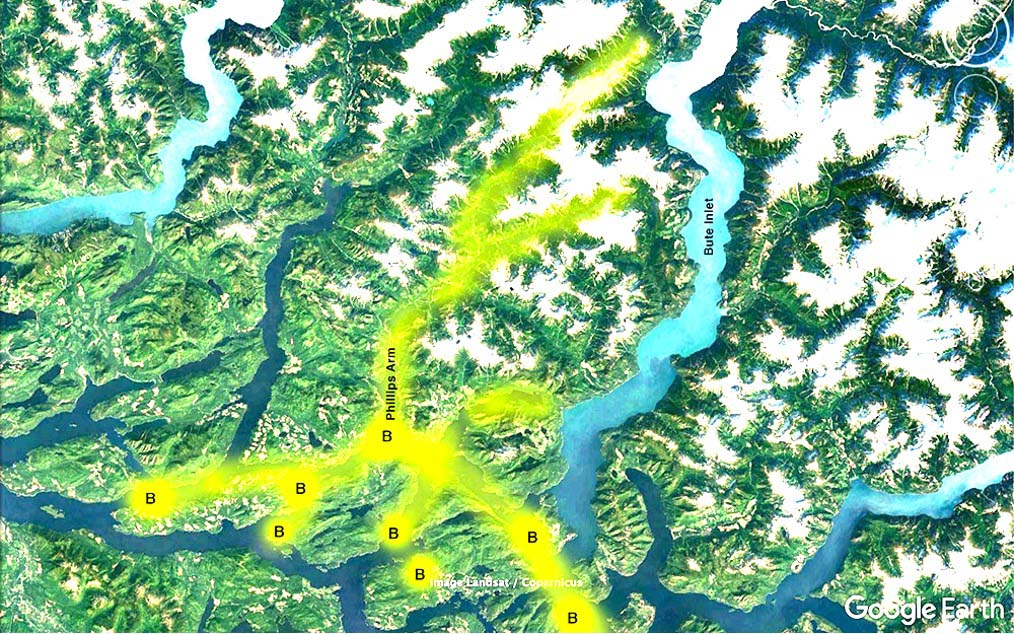

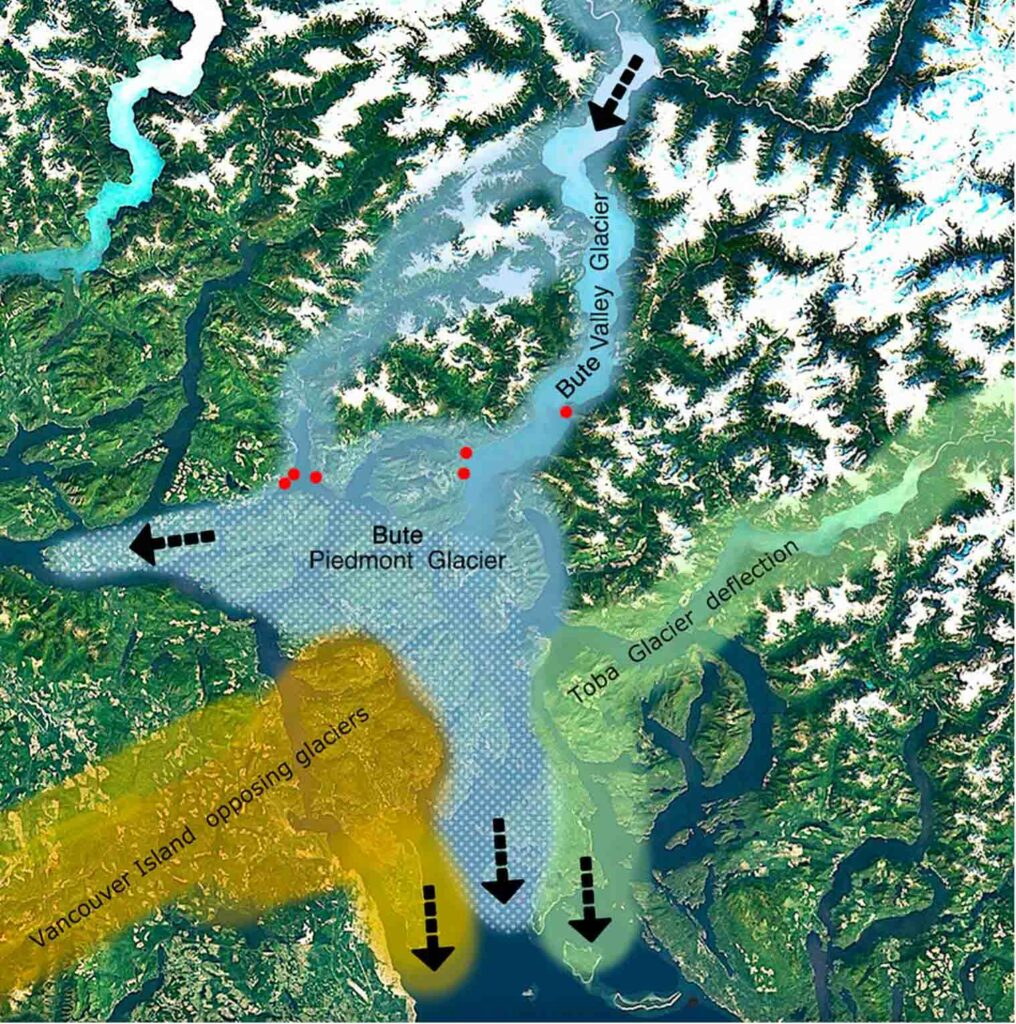

In light of the above, a partial ice-flow map suggests itself (Fig.47. “B” indicates selected Buchia locations).

The northeast trending valleys beyond the head of Phillips Arm clearly join the upper reaches of Bute Inlet, which means that they were part of the same branching system of valley glaciers and that they shared the same place of origin. As demonstrated: the Phillips Arm glacier transported Buchia fossils – it makes no sense to think that the Bute Glacier should not have done the same.

The next step in our investigation has to include another close look at the boulder beaches of Bute Inlet. The same reasons that caused us not to be successful in finding Buchia-erratics up Phillips Arm in 2019 must apply to Bute Inlet.

Thinking about the dynamics of glaciers, a few basic principles became clear and could be applied to our situation in a most meaningful way: Since having found Buchia samples east of the so-called “magic line,” we now know that this line is not absolute. Rather it is an artifact of the dynamics of glacial rock transport and a function of the reality that a valley glacier is trapped inside its trough, where it is variously constrained and buffeted by lateral glaciers joining the main stream from numerous side-valleys, resulting in a concentration of its original rock content in a so-called medial moraine, which, when the ice eventually melts, deposits its contents in the middle of the resulting fjord, that is to say: in its deepest part. By contrast, the front of a valley glacier, exiting its confines into a more spacious area of lower profile, changes into what is called a piedmont glacier (it “pancakes,” as some geologists have called it), and will spread laterally to distribute its rock load over a wide area, where most of it does not end up under water. In our case, this area of lower profile is what we today refer to as the “Discovery Islands.”

Before we got ready to re-search Bute Inlet, we enjoyed a visit by Jim Haggart and wife Renee, during which he, the expert himself, earned a spot in the Fossil Book of Fame by finding Fossil #119 on a beach on Read Island (Fig.48).

Fossil #119 is a modest find (Fig.49), but the real thing nonetheless, and one that made Jim quite happy!

Internal Buchia mold on top, external mold on the left.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

These much-quoted lines from T. S. Eliot’s poem “Little Gidding,” taken out of context by many an author and happily applied to all manner of circumstances, work exceptionally well for the situation we were facing at this point in our decades-spanning search for the origins of the Buchia-erratics.

A long and at times meandering storyline, now coming full circle and forcing our attention back onto the first suspect we investigated many years ago: Bute Inlet. Initially somewhat misguided and unlucky in our earliest searches, we were wandering far afield. In the process, we developed a more complete image and understanding of glacial actions and the movement of erratics than we would otherwise have achieved.

After the evidence presented by the previous year’s finds at the mouth of Phillips Arm, our usual team of explorers, Carrie and Barry Saxifrage, the author Christian Gronau and Aileen Douglas, set out on the first targeted field trip up Bute Inlet on July 23, 2021. The boat journey was timed to take full advantage of the rising afternoon tide that day, and we spent a total of 8 hours looking at steep boulder beaches in this fjord with generally near vertical shorelines.

Beach access was made difficult by kelp covering the boulder surfaces, on top of which the waters of Bute Inlet had deposited slippery layers of fine mud (“glacial flour”), possibly enhanced by the recent (November 28th, 2020) massive landslide near the head of the fjord (Elliot Lake down Southgate River). But this was the beach where Aileen broke “the Bute Spell.”

Fossil #121 represents the first solid evidence that Buchia-bearing erratics had travelled down Bute Inlet (Fig.51).

A couple of bays farther north, an abandoned logging show made beach access a lot easier (Fig.52):

In short order, Carrie added Fossil #122 to the list: a typical, immediately recognizable Buchia cobble (Fig.53).

Barry’s contribution soon followed. Fossil #123 is another example of the less common, though by now familiar, dark sandstones, containing remnants of Belemnites, conspicuously revealed after splitting the rock (Fig.54).

Long hours of at times difficult beach exploration had resulted in finding only three modest fossil specimens, but their importance cannot be overstated: they establish Bute Inlet indisputably as a conduit for the transport of Lower Cretaceous Buchia-erratics and gave us the answer to a question we had first asked nearly 30 years ago!

Meanwhile, the Healeys enjoyed great success in their beach-combing ventures and added numerous specimens to the growing catalog: Fossils #117, 124, 125, 126. 127 and 128!

Numbers 124 to 127 are pictured below (Fig.55).

Glacial movements can be complex, and even though we were confident that the three specimens found north of Bute Inlet’s terminus were solid evidence, we needed to find proof farther up the fjord.

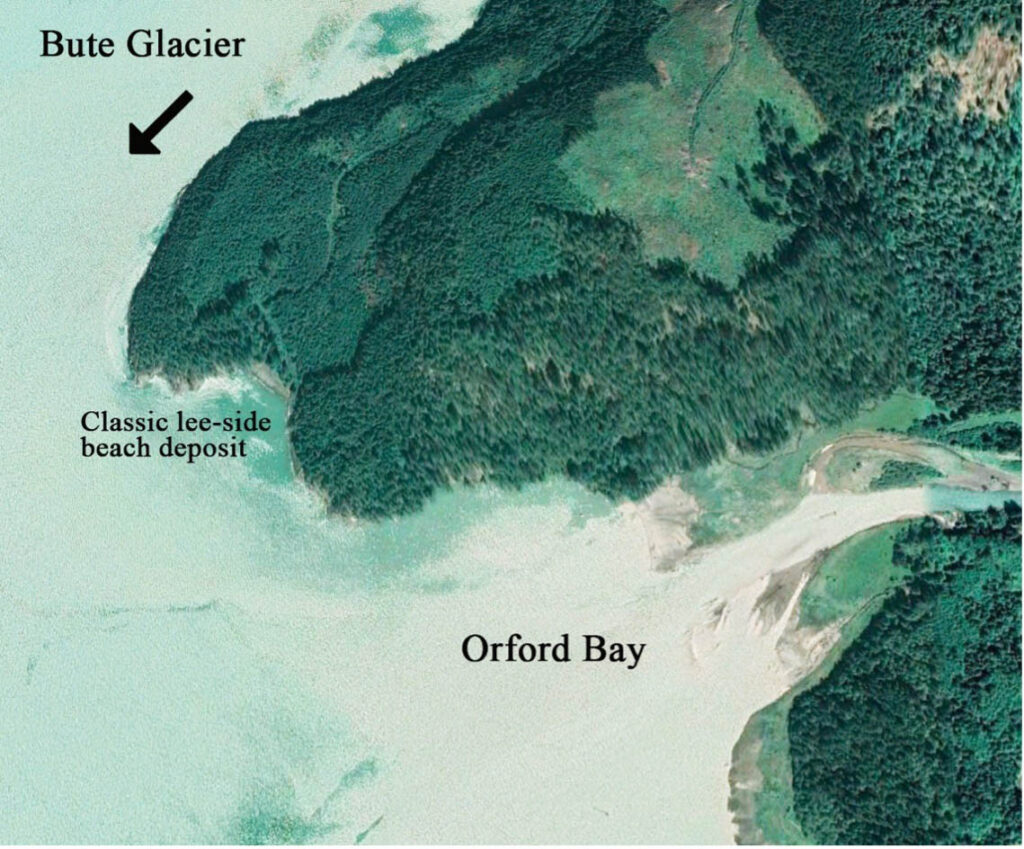

When we set out again, on August 3, 2021, for our second Bute Inlet investigation, we were prepared for spending a lot of time looking at and turning over rocks, hoping for positive results, but expecting little. We stopped at numerous beaches, without much luck, until we had moved up-inlet as far as Orford Bay, where the Orford River enters Bute Inlet from a classic U-shaped glacial valley, which would be called a “hanging valley” if it weren’t for the fact that Bute is flooded by the ocean up to the bottom level of the Orford Valley (Fig.56).

We noticed a shallow bay on the northern flank of the river mouth (Fig.57) covered in small boulders and cobbles. We immediately recognized the location as a typical lee-side deposit, where the Bute Glacier had overridden an obstruction in its path and dropped some of its rock load behind it.

It did not take Barry long to find Fossil #129. A little while later the author added Fossil #130 (Fig.58).

Two small cobbles of similar lithology and Buchia content, albeit of different style in their fossil presentation. Very unassuming, yet of highest significance!

This would be a good moment to take a breath, have a pause and reflect on what has been accomplished – but let’s just say that with the solid establishment of Bute Inlet as a major Ice Age conveyor belt of the Buchia-erratics, we can now with reasonable confidence look towards the Potato Range in the Chilcotin as their source, probably their only one.

We are able to create this map (Fig.59), and its simplicity is comforting. Details remain in question and more work needs to be done, but for now we have some clarity:

Pale blue demarcates the area where Buchia-erratics are common. The red dots show the locations of the recent important fossil finds. The fact that no Buchias have yet been found on Quadra Island is explained by the action of opposing Vancouver Island glaciers, indicated in orange. Toba, Bute and the southern Vancouver Island glaciers were all channelled down the Strait of Georgia, while parts of the Phillips Arm glacier and all of the Loughborough glacier were diverted west, up Johnstone Strait.

Our story has a conclusion – but it remains a never-ending one.

The story continues, because more specimens of interest continue to be contributed… While adding locations beyond the known range of Buchia-erratics is the priority at this point, some of the following finds are of interest, because of their aesthetic appeal, their unusual fossil content or their value as Museum display pieces.

Hannah Healey contributed two more specimens, as the 2021 season started to wind down.

Fossil #132 (Fig.60), because clearly not Buchia, got Jim Haggart fairly excited.

Jim identified the shell fragments as belonging to the bivalve Inoceramus colonicus, an index fossil of some significance. Because the species is 10 million years younger than our familiar Buchias, and has not been recorded anywhere between its type location in California and its northern occurrence on Haida Gwaii, this find extends the stratigraphic (time) range of the erratics we are finding, and it adds a location to I. colonicus occurrences.

It will be interesting to get the results of Jim’s more detailed investigation.

*****

Johannah Paradis’ boys added a few pieces to the catalog. Since our last visit, Kai and Jack picked up three more Buchia examples on Maurelle Island beaches, the final one even smaller than David Ellingsen’s #63.

Team Buchia closed the season with Fossils #138, 139, 140 and 141, all of them small pieces, and all of them with unusual fossil content or uncommon sediment texture.

Fig.61: Not Buchia, perhaps ammonite. Fig.62: Buchia and Bathysiphon. Fig.63: a tiny (0.7 mm diameter) coral-like fossil. Fig.64: Buchia (on backside) in very coarse matrix.

Jan Healey started the year 2022 effortlessly with two fossil finds, the first one from the southern tip of Read Island, the second from the New Churchhouse site.

Her enthusiasm infected two young friends, visiting from Vancouver, and resulted in two noteworthy additions to the Fossil Book of Fame and the Museum collection.

Jessica Cunningham responded to one of Jan’s “show-and-tell” events by casually mentioning that she had found a “much bigger rock” with fossils in it. This bit of information and a photograph Jessica had taken enabled Team Buchia to go looking, and it was Aileen who first laid eyes on the specimen on the northeastern shore of Marina Island, August 2022. Fossil #144 (Fig.65) did not disappoint.

It took the combined effort of Barry, Carrie, Aileen and myself and some old-timer ingenuity (i.e.: as long as the rock is under water, its weight is nearly cut in half) to move the ca. 120 kg boulder onto our boat’s transom, to be ferried to the Cortes Bay boat ramp and then be transported by dolly and car to our homebase for cleaning, and on from there to the Museum porch where it found its place of honour.

These exploits are commemorated by two Roy Hales interviews and broadcasts, accessible via these two links:

Cortes Currents – How Fossil 144 Came to the Cortes Island Museum

Cortes Currents – Glacier-borne Fossils in the Discovery Islands

Only a week later, Jessica’s sister Emma Cunningham joined the Healey’s on a boat outing to the Rendezvous Islands. Following the example of the experienced company she found herself in, she succeeded in retrieving a small boulder from the intertidal zone of the beach. Fossil #145 was heavily encrusted with barnacles, but it clearly showed the presence of fossil content (Fig.66).

After some serious cleaning by the author, the rock revealed its unexpected and stunning fossil content (Fig67).

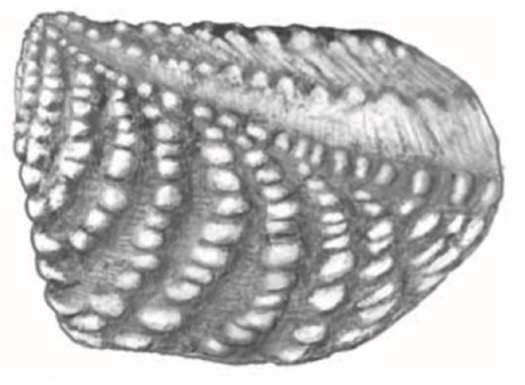

While the specimen does not show great Buchia density, it has two dramatic shell impressions of a trigonid bivalve, identified by the expert in the field, Dr. Michael R. Cooper, as belonging in the genus Yaadia (Fig.68).

Hannah followed in short order and concluded her fossil-finding season for the year with Fossil #146 (Fig.69).

Four more fossil finds completed the year, with the last specimen picked up by Jan on southern Read Island, achieving the grand total of #150 fossil erratics found to date!

Appendix

List of Contributors in Chronological Order

Team Buchia in bold; in parentheses (number of contributions)

Mike Melnechenko, ca.1990, brought to our attention 1994, (1)

Hubert Havelaar, 1998, (10)

Kathryn True, 2000, (1)

Brad Wicks, ca. 2000, sunk 2005, salvaged 2011, (1)

Niko Leader Mense, 2002 and 2007, (2)

Brent Petkau, 2002, (1)

Barry Saxifrage, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2019, 2020, 2021, (44)

Aileen Douglas, 2003, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2019, 2020, 2021, (19)

Debbie Thompson, 2004 and 2008, (3)

Mike Sullivan, 2004, (1)

Iris Steigemann, 2004, lost, (1)

Kathleen Pemberton, 2005, (1)

Gary Block, 2007 and 2008, (2)

Christian Gronau, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, (23)

Thea Block, 2008, (1)

Carrie Saxifrage, 2008, 2011, 2019, 2020, 2021, (8)

Robin Saxifrage, 2008, (1)

Dave Hughes, 2008, lost, (1)

Jim Shaw, 2010, (2)

David Ellingsen, 2015, (1)

Asha Harvey, 2017, (1)

Jan Healey, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, (10)

Hannah Healey, 2019, 2021, 2022, (7)

Jonah Richter, 2019, (1)

Agnieszka Richter, 2019, (1)

Johannah Paradis, 2019, (1)

Kai Sutherland, 2019, 2021, (6)

Jack Sutherland, 2019, (2)

Sabina Leader Mense, 2020, (1)

Jim Haggart, 2020, (1)

Carey Healey, 2021, 2022, (2)

Jessica Cunningham, 2022, (1)

Emma Cunningham, 2022, (1)

If you enjoyed the story, but missed Part One – enjoy now Part One.