Part One

— Dedicated to the trusty members of Team Buchia: my life-partner Aileen Douglas and Barry & Carrie Saxifrage —

With special thanks to Gina Trzesicka for her invaluable help in putting this story on the Cortes Museum blog site.

“I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

— Isaac Newton Said to have been uttered “a little before he died.”

Whether Newton actually uttered those apocryphal words or not, they speak the truth, and they express a humility that behooves any observer at the shores of the cosmic ocean, the enormity and antiquity of which even Newton could not imagine.

For all practical purposes, the World and all the wondrous things in it, and all the fascinating subjects to observe, study or play with, are infinite. They are all interconnected, one leading to the other, and a hundred lifetimes are not enough to touch upon them all, even ever so briefly. And like Newton before us, we don’t even know what “all” means, or how vast the undiscovered ocean of truth might be.

The following story, small though it may be, is, quite literally, about finding “a pebble on the seashore” and playing with it, and others like it, for nearly 30 years.

Note: all specimens referred to in this account are catalogued and described in some detail in the Museum ring book titled “Granite and Fossils.” The book is available for perusal at the Cortes Island Museum and Archives Society at 957 Beasley Road, Mansons Landing, Cortes Island, B.C. It is also accessible online here: Granite & Fossils – Volume One and Granite & Fossils – Volume Two

Fossils – Never-ending Story – Part One

The story began a long time ago, with my complaint to a friend and once neighbour and colleague: “What am I doing here? I am a palaeontologist, and Cortes Island is just a big pile of granite. There are no fossils here!” To which Don Melnechenko replied: “Yes there are – Mikey found one.” And indeed, Don’s son Mike had: “Cortes Island Fossil #1” (Fig.1).

This was unexpected news indeed, and Dr. Jim Haggart, senior palaeontologist with the Vancouver branch of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), was contacted in 1994 – and he has been part of the story ever since. His expertise lies with Cretaceous mollusc fossils, and he unhesitatingly (though cautiously) identified the shell remains in Mike’s pebble as Buchia? sp. cf. keyserlingi, a bivalve of Early Cretaceous age (ca. 130,000,000 years old).

The specimen contains several precise shell impressions in a dark sandstone pebble. It was found on the north shore of Gorge Harbour, among a plethora of other loose pebbles, cobbles, and boulders (what geologists refer to as “drift”). They all are part of the chaotic deposits left behind when the glaciers of the past Ice Age melted. Cortes Island is rich in glacial deposits: all the local beaches represent great collections of highly varied stones, most of them beautifully rounded, brought here by the movement of ice. Rocks transported by glaciers in this manner are called “erratics.” ERRATICS – BY CHRISTIAN GRONAU (in blog).

Mike’s fossil (Fig.1) is an erratic – albeit a very small one.

The immediate question arises: “where did it come from, originally?” The complex fjords and channels of the B.C. coast represent the trackways of valley glaciers, advancing from the high Coast Mountains in the east, until they spread out on coastal plains, turning north to carve Johnstone Strait, and turning south to fill the Strait of Georgia, some even reaching the open Pacific Ocean. A complicated labyrinth of glacial pathways eventually, at the maximum of glaciation – frozen solid by the overburdening miles-thick Cordilleran ice (Wiki) sheet.

Many travel routes could be imagined for our singular erratic. Some hypotheses were immediately favoured (always a dangerous thing), promoting a local origin and correlating Mike’s find with occurrences of Buchia fossils in situ elsewhere in the province. Various possibilities were debated, and it became clear that finding more fossiliferous erratics was essential to delineating the travel routes of the responsible glacier or glaciers.

Word was spread; photos were posted; the one precious specimen was shown around. Responses followed.

From such inconspicuous beginnings, 30 years later, the number of recorded fossiliferous erratics has risen to over 150! Far too many to be accommodated in this account. Every person who contributed specimens and observations to what became known as the Fossil Book of Fame (or The List, for short) has to be highly commended, if only for the simple yet uncommon fact that they are observant and are paying attention. A list of the names of all contributors can be found in the appendix.

The more spectacular specimens as well as those of special significance to our story will be mentioned in this blog. I shall try to deliver a chronology that reflects the winding path our investigations followed, its hesitations and reversals of direction, its formulations of working hypotheses and their subsequent abandonment in favour of new ideas inspired by new evidence.

That’s the way science works: by trial and error, not by trial and success.

The scientific method is brilliant when it comes to disproving fallacies: by recoiling from falsehood, scientists have slowly been backing into the truth. That is a sometimes-awkward position to be in and even harder to communicate: science sees what is false much more clearly than what is true (and is despised for it by those clinging to popular delusions, deeply held beliefs, and craving for certainty).

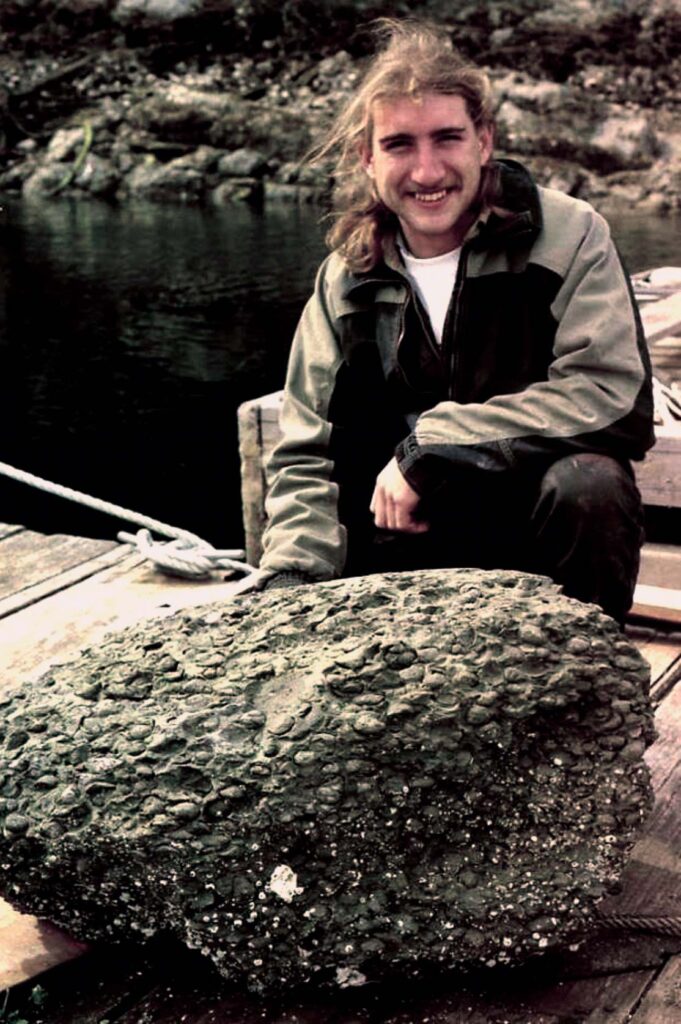

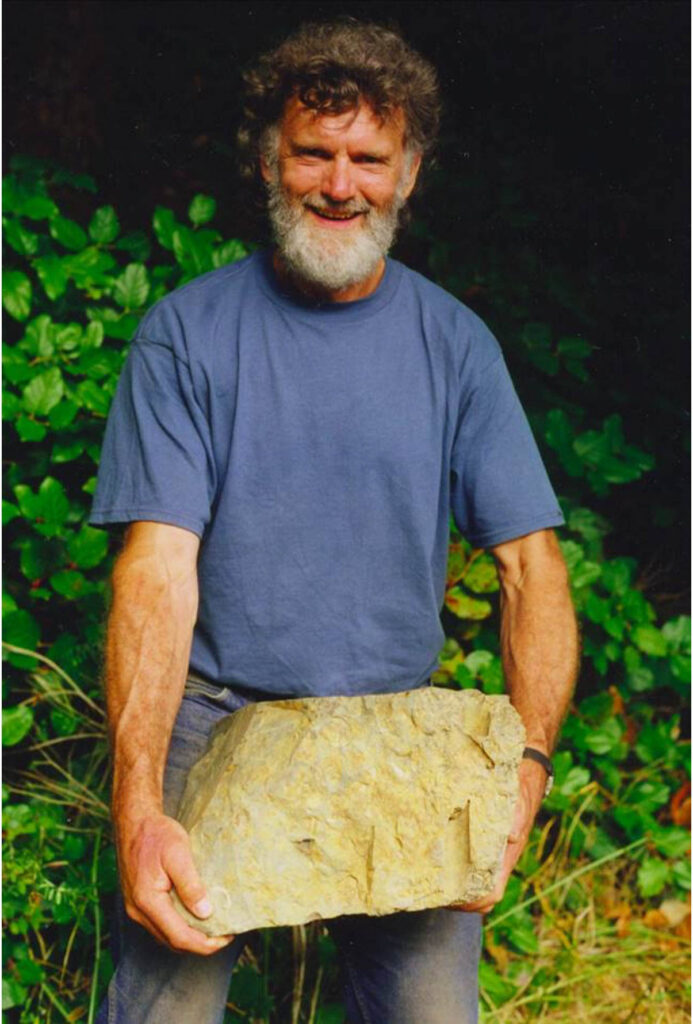

Fossil #2 could hardly be any more different than #1. If Mike’s pebble could be held between two finger tips, it takes the stature of Hubert Havelaar to lift a boulder like #2 off the ground (Fig.2).

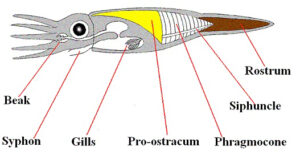

Large and bound by parallel fracture planes (joints), weathered to a rich light ochre, the piece contains, again, several fossil remains of Buchia bivalves, but more prominent are the molds of four belemnites! Belemnites are a group of extinct cephalopods, superficially resembling squid, but having an internal skeleton (Fig.3), shaped like a long torpedo, called the cone, consisting of several parts and made of calcium carbonate.

To this day, Fossil #2 is the only specimen in hand that was found inland – hence the ochre weathering crust, not removed by wave action as in all the other beach-worn pieces. To this day, Hubert’s find remains unique.

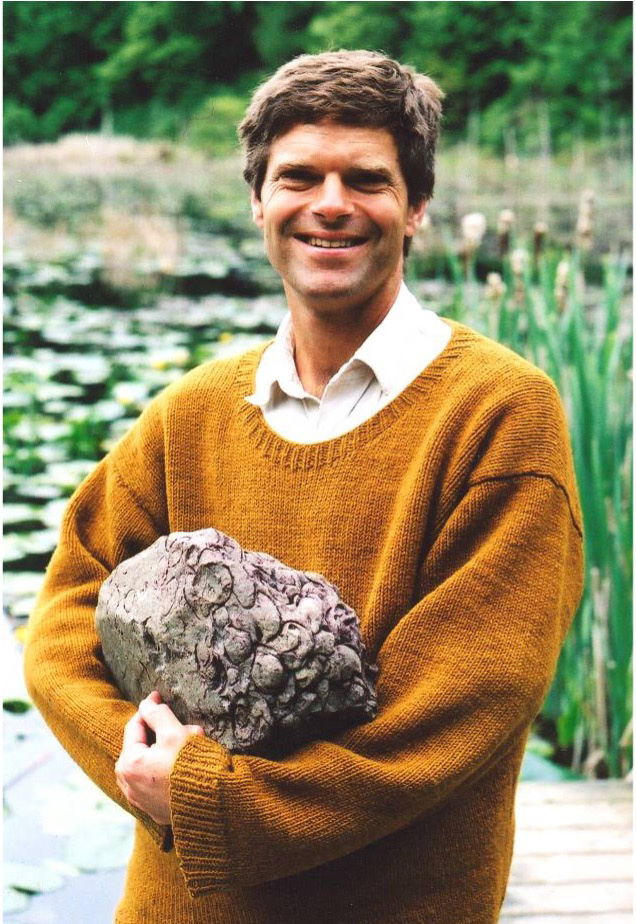

Fossil #4 has a bit of history: In 2001, we were approached by Brad Wicks, who had found a boulder rich in Buchiafossils in the intertidal zone of Refuge Cove, West Redonda Island. He had removed the large rock from its original resting place onto a wooden float, anchored in the cove (Fig.4).

This specimen was again unlike any of the previous finds, and remains, at about 200 kilograms, the most massive piece to date. It is completely packed with Buchias, making it what is known as a “shell-supported coquina.” The piece is on permanent display at the Cortes Museum – though the story of how it got there is a slightly convoluted one: In 2005, Brad’s old raft caved in, and his precious boulder plunged to the bottom of Refuge Cove! It took us several years and the help of a hardy crew of volunteers, to mount a recovery expedition.

In 2011, Mike Moore, his trusted ship Misty Isles and deckhand Bryce Therrin came to the rescue. Sporting his scuba gear, Mike was able to locate the sunken treasure and roll it into a cargo net we had provided and then hoist it aboard. A slightly nerve-wracking enterprise, considering that the winch’s hook had snagged not the main line, but only the 3/8-inch rope used for tightening the net! (Fig.5)

With the help of Nancy & Ray Kendel, the boulder was put on display at the Museum, and, finally, in 2021, it was moved to a place of honour on the outdoor porch of the Cortes Museum. (Fig.6)

Fossil #4, in the right foreground, stands nearly a metre tall and appears to be completely and evenly packed with Buchiafossils. Using an average volume for the bivalves of about twelve cubic centimetres, the boulder contains approximately 7,000 Buchia fossils! Aileen Douglas is looking on.

Note also Hubert Havelaar’s angular rock (Fossil #2) sitting on its cedar stump.

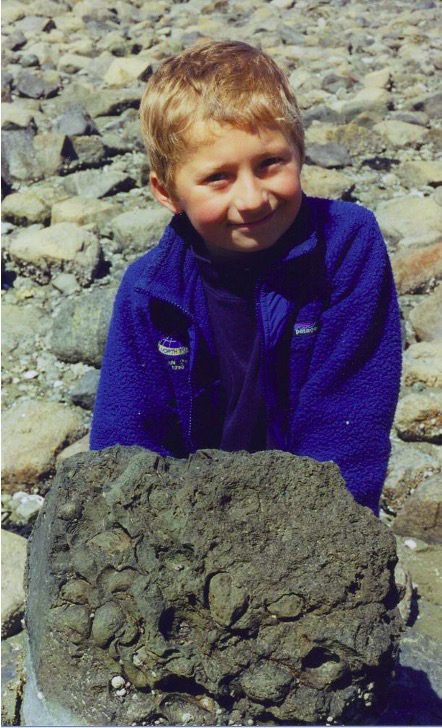

Fossil #5 (Fig.7) is impressive and instructive, combining different sedimentation styles in its bulk. It was found in 2002 on the Cortes Island side of Plunger Pass by 7-year-old Niko Leader-Mense, who still holds the record of youngest contributor to the growing list of Buchia-erratics.

Fossil #7 (Fig.8), found in 2003 on a boulder beach just north of Carrington Bay, aside from being a remarkable piece in its own right, marks the moment when Barry Saxifrage became a member of “Team Buchia” (Fig.8). Barry has been part of the Buchia research project ever since and continues to be the most prolific contributor of specimens to this day.

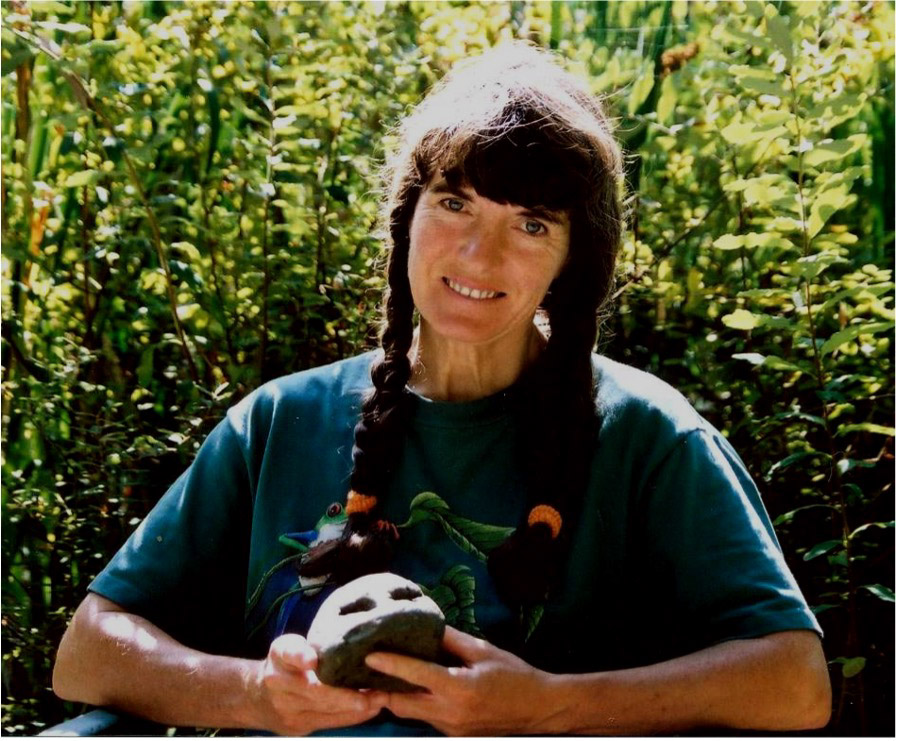

Fossil #8, found near the previous piece (also in 2003), may not be as showy, but it deserves mention because it inaugurates Aileen Douglas as a card- (fossil-) bearing member of Team Buchia (Fig.9):

Most pieces brought to our attention during the following years were rather inconspicuous small rock fragments from various beaches, until, in 2007, Niko located splendid Fossil #25 (Fig.10) just a few yards from where he had found Fossil #5 five years earlier!

A Saxifrage family tradition was an annual “Camp Carrington” summer outing, and, for several years, the combined efforts of keen eyes, young and old, contributed many specimens to the Buchia list.

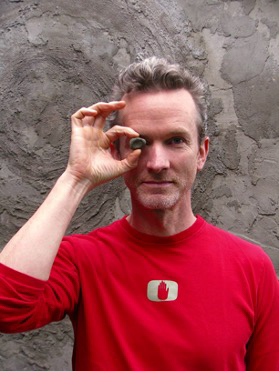

Eventually, even the original instigator of this research project and author of this blog (Fig.11) managed to contribute a fossil by visiting the productive location in 2007 – albeit it was not a Buchia! By then, the fossil count had reached 31 (Fig.12).

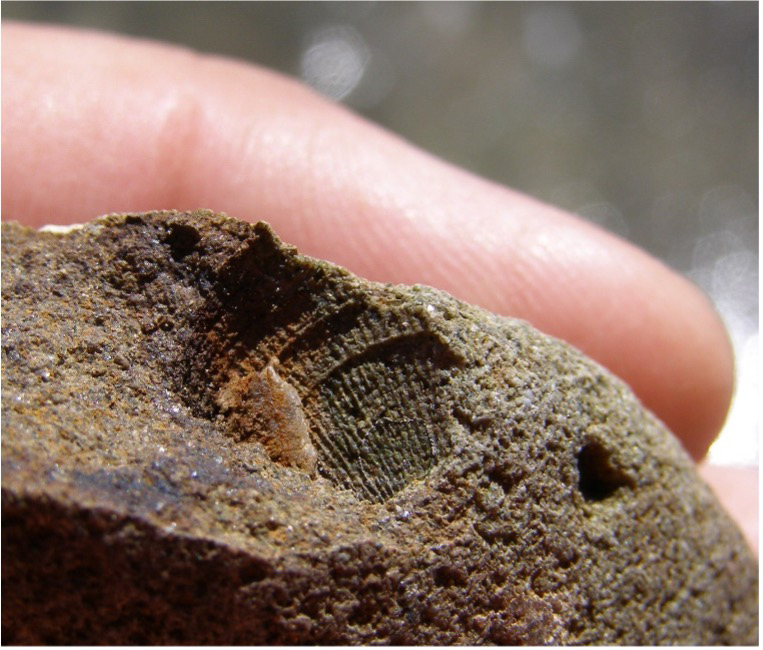

The impression of a bivalve with radial sculpture and prominent growth lines. A tentative identification was made, but the specimen had to be sent to the GSC for clarification.

On 10-Nov-08, at 10:31 AM, Jim Haggart wrote:

My verdict on the odd little “Aucellina” bivalve that you sent last winter is that it is just a simple, plain cucullaeid (e.g. Lopatinia) or glycymerid. Sorry about that…

Sadly, before the question could be settled, the actual specimen was lost in the labyrinthine bureaucracy of the GSC, where it had languished for more than a year…

The following year, 2008, Barry Saxifrage’s Camp Carrington report began like this:

“Our annual outing to Camp Carrington yielded the usual suspects …”

Well, not quite: hidden among the “usual” Buchias and obscured by barnacle growth, a small beach pebble contained the surprise of Fossil #32 (Fig.13):

********

By now, a certain pattern of distribution began to emerge: no Buchia-erratics had been found on the east side of Cortes Island – despite considerable efforts by Barry Saxifrage. It became clear that the glaciers responsible for the transport of the fossiliferous Lower Cretaceous sandstones must have come out of Bute Inlet, not Toba. The geological maps show two parallel bands of sedimentary rocks cutting across Bute, assigned to the Lower Cretaceous Gambier Group (lKg). Even though these rocks are described as lightly metamorphosed volcanoclastics and no mention is made of fossil content, it behooved us to take a closer look at these strata, being coeval to our Buchia sandstones, after all. Also: If the formations in question turned out to be source rocks for Buchia-erratics, the “favoured hypothesis” of local origin, mentioned in the introduction, would be supported.

During August 2008, our team set out on the Misty Isles, skippered by Mike Moore and accompanied by Robin Saxifrage and Thea Block, to investigate lKg…

Bute Inlet

We located the Gambier Group rocks without any difficulty at all four intersections with the steep walls of Bute Inlet (Fig.14).

Steeply inclined sedimentary strata, metamorphosed into phyllites and even schists, but no layers of sandstone of the kind our Buchia fossils had been found in. In short: lKg did not deliver: no fossils, not even the correct rock type. After two days of somewhat frustrating explorations, we decided to leave the fjord and turn towards more promising locations.

Our departure was observed by a lone black bear (Fig.15) – and we were wondering: does he know what kind of rock he is standing on?

After spending the night in Owen Bay, the morning dawned early and full of expectation. As if leaving Bute Inlet had allowed us to cross a “magic line,” the following two days were highly successful.

As the tide started to drop, Aileen found the first Buchia-erratic of the trip, Fossil #35, a medium-sized boulder, containing at least two different species of Buchia (Fig.16).

In neighbouring Diamond Bay, Carrie (Fig.17), located Fossil #36, a large black boulder, packed with Buchia fossils (Fig.18).

A noteworthy specimen was found by Robin at the old Churchhouse site on Sonora Island: Fossil #39 (Fig.19) is a small boulder of very black sandstone, owing its colour to a high concentration of magnetite grains, making the rock magnetic.

*********

The two days spent west of Bute Inlet resulted in a total of eleven fossiliferous erratics being found – the author only contributing one (much to the delight of young Robin).

“There are no negative results in research” – or so the saying goes. We did not find any evidence of Buchia or even the typical Buchia-bearing rocks along the shores of Bute Inlet. Instead, the notion of a “magic line” made us look northwest, into the labyrinth of channels and islands, wondering whether the source rocks (the sought-after “motherlode”) might not be hiding somewhere up there.

Some time ago, in 2006, Barry Saxifrage had found a Buchia sample in Hemming Bay, on East Thurlow Island. At the time this only confirmed our conviction that Toba Inlet was not a travel route for the erratics we were pursuing, but now, after the discouraging results of our Bute expedition, the location seemed like an endorsement of the “magic line” concept.

It was to be a while before we would have the means to explore that idea more thoroughly.

More Buchia-erratics were found in the following years, several worthy of inclusion in this report, but, for the longest time, our quest for the “mother lode” would yield no answers…

Hubert Havelaar (of Fossil #2 fame) relayed rumours of “lots of fossils in Big Bay on Stuart Island” and offered to take Aileen and myself in his sailboat Osprey to have a look. In September of 2010 we did just that. The excursion was most enjoyable, as well as quite successful, resulting in several finds in Big Bay itself, as well as in surrounding areas – including this beauty, picked up by Aileen (Fossil #56, Fig.20):

Hubert, nonetheless, felt that he had let us down, so he stopped for the night in Burdwood Bay, Read Island, and we visited Tom Gilbert, who had been the source of the Big Bay “rumours.” Tom, after admitting that his Big Bay recollections are 20 years old, made up for any shortfalls (real or imagined) and rowed us in the failing light of the evening across the bay to show us this (Fossil #59, Fig.21):

The next morning was sunny, and we went to get a good look at Fossil #59 (Fig.22).

Arguably the most spectacular Buchia-erratic of them all, this elongated boulder is 1.20 metres in length. Jam-packed with Buchia shells, it rivals Fossil #4 in the number of fossils it contains.

The blackness of the rock is like Fossil #39, and, indeed, it too is magnetic. (Fig.23)

As the rope, visible in Fig.21, hints at, Jim Shaw, below whose house the specimen rests, has some proprietary feelings towards the specimen and has yet to be persuaded to have it on permanent display at the Cortes Museum (where a place for it is held in reserve).

The success of the Big Bay expedition made us re-evaluate our Bute Inlet experience. After all, Stuart Island sits directly at the mouth of that prominent fjord.

Glenn Woodsworth, retired GSC geologist and, with J. A. Roddick, co-author of the geology map used throughout this write-up, thinks the erratics might have come all the way from the Potato Mountains.

The Homathko River, which empties into the headwaters of Bute Inlet, drains the western flank of the Potato Mountains, which lie between Tatlayoko and Chilko Lakes, some 200 kilometres north of Cortes Island. This drainage pattern reflects the course of ice-flow during recent glaciation events.

The western Potato Mountains have extensive exposures of Buchia-rich sequences.

If this latter scenario were true, we should have found Buchia-erratics during our Bute Expedition.

Of course, as the shrewd saying goes: “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

Steep-sided Bute does not have the extensive boulder beaches that proved so productive further south; maybe we didn’t look long and hard enough in 2008; maybe we should look again.

Another useful approach to solving the mystery would be to compare Buchia collections from the Potato Mountains with the erratic material we have amassed locally. A personal communication by Glenn Woodsworth falls into that category: “The magnetic Buchia is very cool. I’m not aware of any such fossiliferous rock east of the Coast Mountains,” in reference to Fossil # 59, its blackness, and strong magnetism. This supports the model favoured by Jim Haggart of a Lower Cretaceous inland sea, into which the dark sandstones, containing Buchia fossils, were deposited.

To complicate matters, the two “competing” models are not mutually exclusive!

Some erratics may have come all the way from the Potato Mountains, while others could very well have been locally derived.

This apparent impasse, plus a series of personal family-related distractions, brought a bit of a lull with it. From 2010 to 2017 only 4 (four!) specimens were added to the catalog! Fossil #61 is noteworthy, because it yielded, after some careful processing, two new non-Buchia bivalves, as well as two belemnite fossils of interesting preservation.

Fig.24 is a phragmocone, with rudimentary chamber walls preserved (refer to Fig.3), and Fig.25 is a dramatically weathered cross-section through the anterior part of the rostrum, suggesting a petrified eye, staring at the observer.

Fossil # 63 holds two records: the smallest fossiliferous pebble found at the southernmost location – at least to date. It had been picked up by photographer extraordinaire David Ellingsen from the south end of Smelt Bay and was (re-) discovered by the author on the windowsill of David’s former Reefpoint Farm studio in 2015.