(All photographs are the author’s unless indicated otherwise.)

Ammonites are probably the most familiar of all fossils. Most people will be able to conjure up some sort of mental image when they hear the word. Ammonite: a coiled shell, a spiral shape embedded in rock… close enough. Or, perhaps, not.

This blog could get very technical–let us avoid that. Let us rather have a brief (and simplified) look at the story and the history of these beautiful and intriguing fossils, and find out, along the way, where our Museum Fossil belongs.

The journey starts in the Precambrian, some 600 million years ago, when the first shelly fossils appear that can be placed, with some confidence, in the phylum Mollusca (snails and clams and squids and their kin).

Not much later, the class Cephalopoda can be distinguished–and in our modern oceans, this group is still present as the familiar Octopus, Squid, Cuttlefish and Pearly Nautilus.

When the cephalopods first showed up, they lived in tiny cone-shaped shells and probably crawled along the ancient sea bottom, much like snails continue to do today. The difference was that the cephalopods partitioned off the ends of their shells and created gas-filled chambers for buoyancy, to help carry the weight of the shell. The broad foot, typical for snails, probably differentiated into numerous tentacle-like appendages early on in the group’s history.

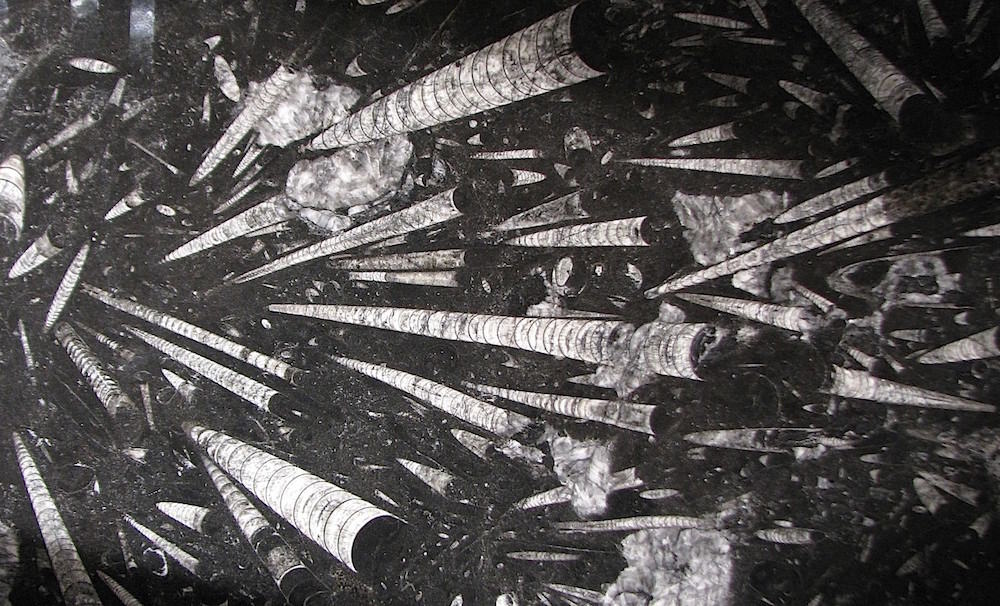

Soon the shells grew larger, and, by the Ordovician, some straight-coned (orthocone) cephalopods (often collectively referred to as Orthoceras: “straight horns”) had reached a length of 5 meters! They were the top predators of their day. Not only by size but also in numbers, orthocone cephalopods were the rulers of the sea for much of the Palaeozoic Era. While they managed to persist all the way into the Cretaceous period, their glory-days were over by the end of the Devonian, when several extinction events took their toll and left spectacular accumulations of fossil shells in many locations worldwide.

Even as the orthocone cephalopods built their dynasty, a different Bauplan was evolving: the “straight horns” started to curl up into “spiral horns.”

Sometime during the Ordovician, the shell curled into a tight spiral, with simply curved chamber walls: the basic design type of the familiar “Nautilus” was achieved. This proved to be a very successful and conservative Bauplan, still represented by the living Pearly Nautilus (Nautilus pompilius and its kin) today.

So there we are: the perceptive reader will have recognized at this point that the Museum specimen is nothing less than the petrified fossil remains of a Nautilus!

It was found by Ian Disney’s father on Sucia Island in the San Juans, in 1926. Based on details of shape and shell structure, the specialists (e.g. Shimansky, 1975) have assigned it to the species of Cymatoceras suciensis. It is from the Late Cretaceous of the Nanaimo Group and ca. 70 million years old.

Come to the Museum and see for yourself!

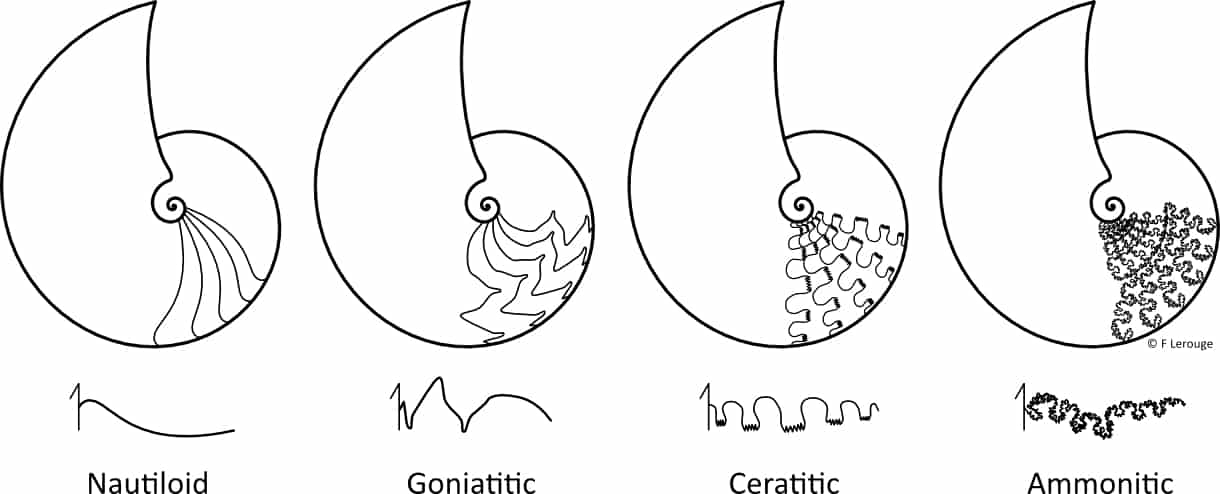

This could have been the end of the story for the nautiloid tribe: having achieved the perfect spiral shape and a lifestyle which, obviously, would serve them well through the very depth of geologic time … But, in the Silurian, a trend developed that would carry on into and through the entire Mesozoic era: the simple no-nonsense chamber walls of the nautiloids began a journey into fractal complexities, nothing short of astonishing.

Probably under pressure from various predators, which were able to crush the protective shells even of the coiled nautiloids, the chamber walls evolved folds and kinks and became corrugated “bulkheads”, adding tremendous structural strength to the shells.

These developments proceeded step by step and, for simplicity sake, only the best known and documented sequence is shown here (Fig 9):

Other changes took place as well, like the shifting of the siphuncle from its original position in the centre to the outer perimeter of the shell, and numerous odd deviations from the spiral shape appeared–but we did decide not to get too detailed or technical…

- Nautiloids experienced their acme in the Ordovician and Silurian periods, but persisted, in gradually diminishing diversity, to the present day.

- Goniatites are typical of Devonian and Carboniferous times.

- Ceratites are the classic Triassic ammonoid.

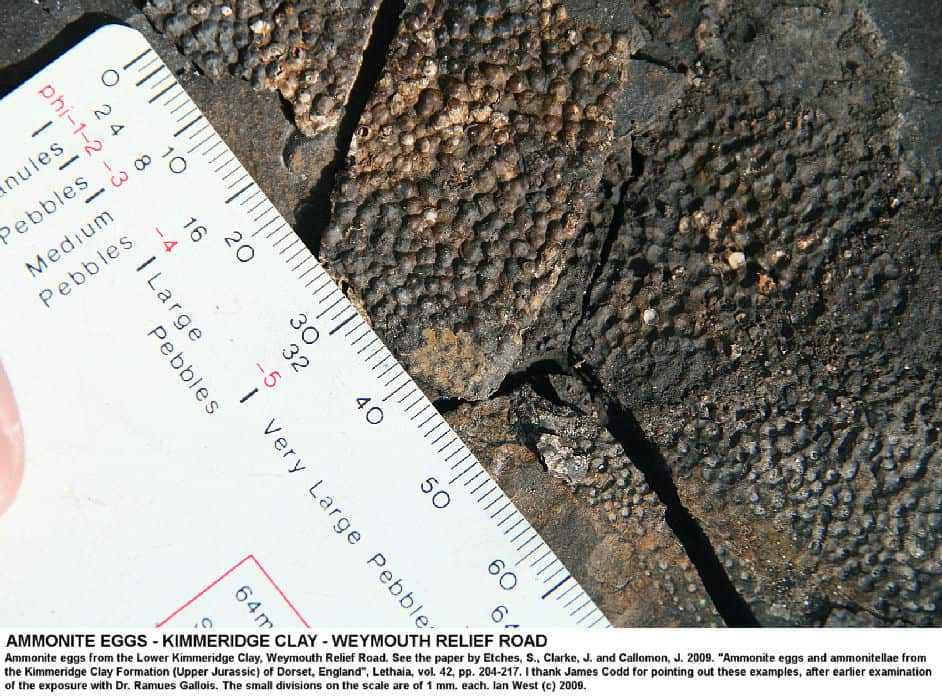

- Ammonites proliferated and lived in untold numbers during the Jurassic and then again in the Cretaceous period, after which their entire tribe, together with the dinosaurs, went extinct.

So it is established: the Museum fossil is a nautiloid and, as mentioned above, has been identified as Cymatoceras suciensis of Late Cretaceous age, ca. 70 million years old.

It is a fine specimen and, perhaps, testimony to the fact that a great design has staying power. Surviving for hundreds of millions of years, the beauty of the Pearly Nautilus has persisted to delight us with its elegant perfection to this very day (Fig. 10).

And finally, just to make sure you know, this is a true ammonite (Fig. 11):