Owls Are the Best Field Assistants in Biodiversity Studies

–

An Appreciation of Owl Pellets

Oliver Pearson, a pioneer in Patagonian mammalogy, always said that owls were his best field assistants during Patagonian surveys. They hunted more species and more individuals than his trap lines, so they were useful estimators of field abundance.

Analia Andrade et al. 2015

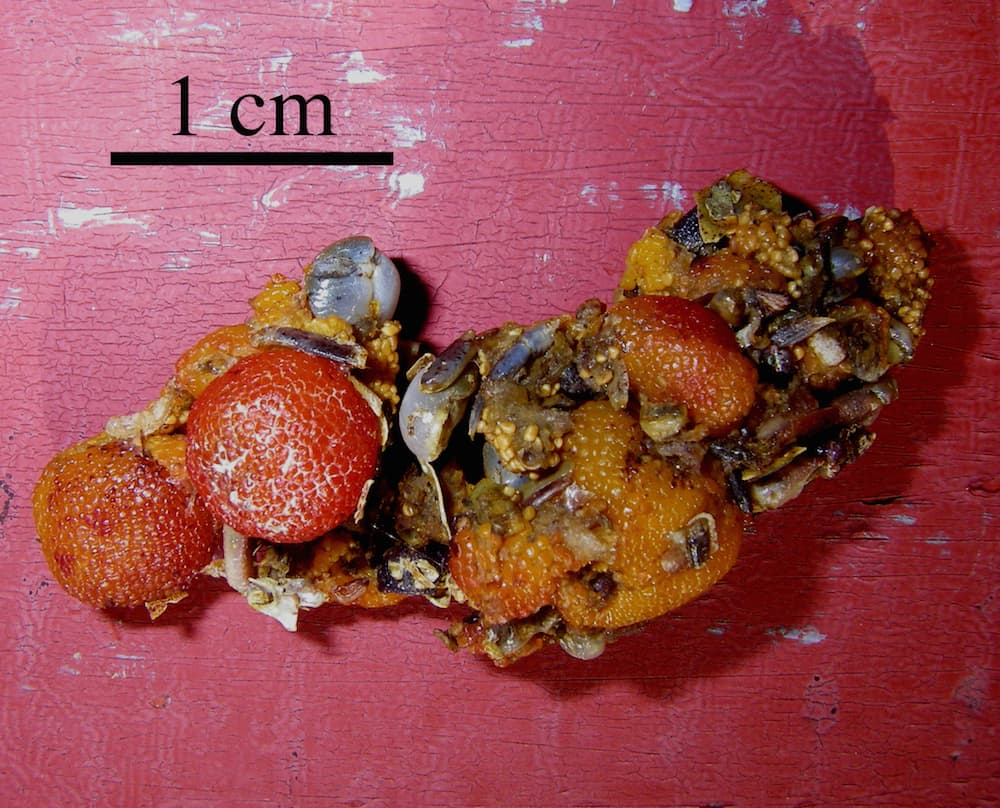

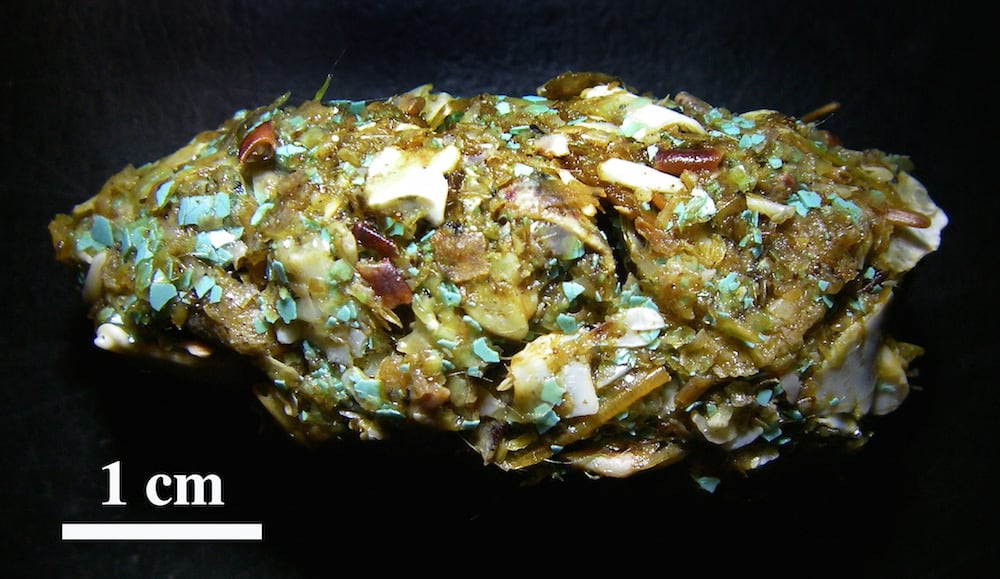

One event to quicken any naturalist’s heart is the discovery of an owl pellet. “Pellets” consist of the regurgitated indigestible remains of an Owl’s prey: bones, fur, feathers and similar items. The concept of regurgitating bones and fur is not very appealing to us humans, but Owls seem to react with apparent satisfaction after successfully ejecting a pellet. The process, aside from eliminating unwanted stuff, has the function of scouring the upper parts of the digestive tract and seems to bring health benefits to the bird. It is remarkable how skillfully the often sharp-edged bone fragments are wrapped in fur and feathers, making the ejection of the pellet as smooth an affair as possible.

Pellets are not always easy to find: here on Cortes Island, with an abundance of trees and often lush ground-cover, a pellet could be just about anywhere, and not necessarily in plain view. In the desert or in the prairies, the situation is much more favourable for the pellet collector: if there is a tree anywhere, Owls will frequent it! (And other raptors too, of course, who may also produce pellets–though in falconry, they are called “castings”.)

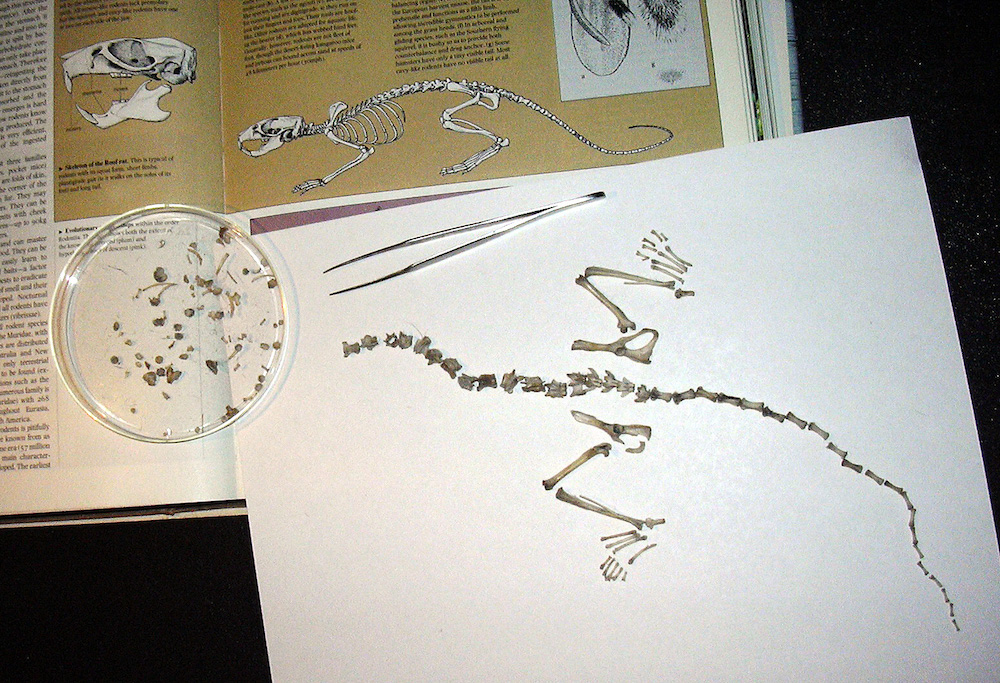

Even a cursory glance at an owl pellet reveals an abundance of skeletal remains, some of which are large enough for easy identification.

The fact that Owls hunt many different species (as mentioned by Oliver Pearson, cited above) means that one never knows what kind of animal remains one might discover in a pellet.

Insect parts are common, and sometimes, as in the case of large beetles, their identity can be ascertained.

One owl pellet we found in the Saltlake Desert of Utah contained the pedipalps (pincers) of a scorpion, which still fluoresced under UV light and could be identified (by experts more knowledgeable) as belonging to the species Anuroctonus phaiodactylus.

Koi farmers have reported seeing Barred Owls dive on their tanks, scarring the backs of fish.

In the Anvil Lake area, we found Crayfish remains (Astacus trowbridgi) in Barred Owl pellets. (This was considered noteworthy enough for publication: Gronau, Wildlife Afield 2:2 December 2005.)

We have observed both Great-horned and Barred Owls actively hunting snakes, and, eventually, we found a pellet glistening with the keeled scales of a Garter Snake.

It may not be generally known, but essentially all birds, from songbirds and sandpipers, through Crows and Ravens, all the way up to Eagles, produce regurgitated lumps. (Mammals, incidentally, are no exception: the famous “hairballs” of cats fall into this category.) The generic (medical) term is bolus (plural boli or boluses), which is Latin for “ball”.

Not much is known about the pellets or castings or boli of small birds: their tiny efforts are easily lost and destroyed, or simply overlooked.

Here are a few examples from birds other than Owls:

The most common and familiar pellets are those of the Barred Owl, which is, of course, the most common owl species on Cortes Island these days. Common or not, it is always exciting to check carefully to see what our “field assistants” (sensu Pearson) have collected. Barred Owls are particularly helpful, since their tastes seem to be very catholic.

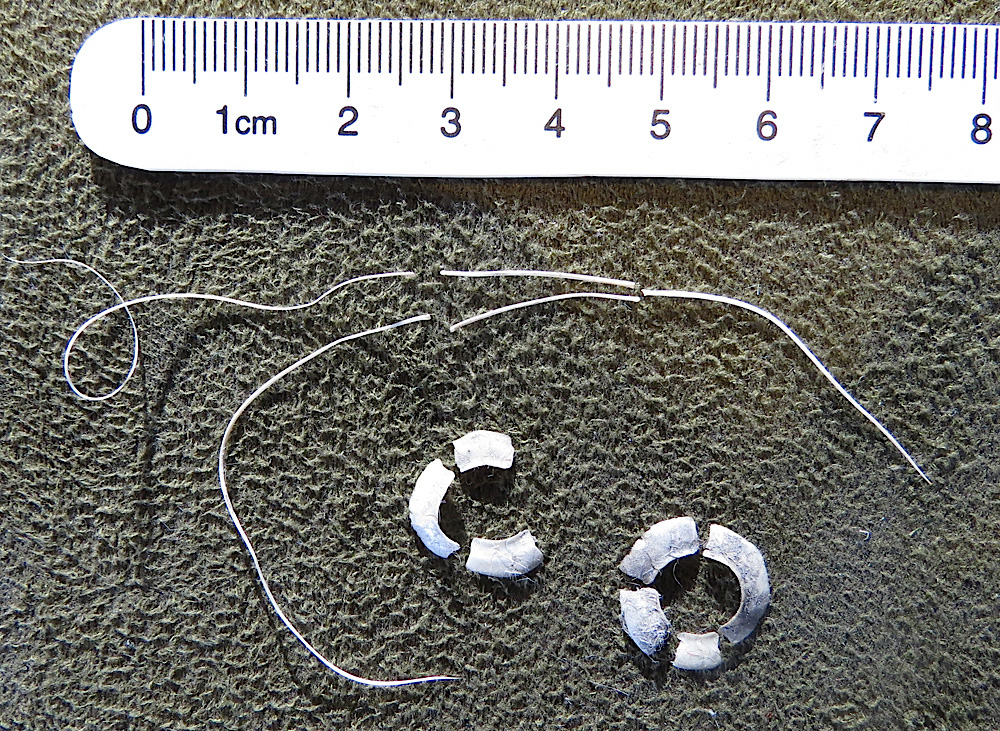

A recent find, aside from familiar Rat leg bones, contained extremely thin and curved bones.

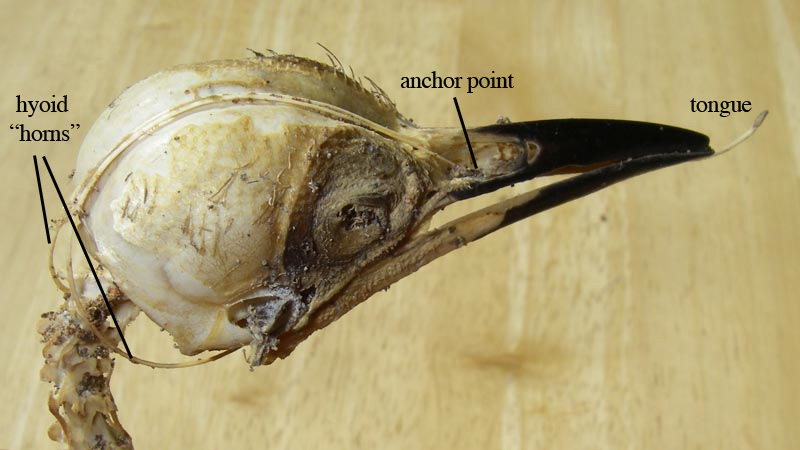

This pellet had to be taken apart to identify those constituents that were not obvious Rat bones. It turned out that the thin bones constituted the entire hyoid bone arrangement (also known as “tongue bones”) of a wood pecker. Measurements suggest that the bird was a Hairy Woodpecker. Also present were the elements of the scleral rings (also called “ossicular rings”) that surrounded the woodpecker’s eye orbits.

As faithful Museum-goers may recall, a woodpecker skull (in this case that of a Northern Flicker) was on display in a comparative-skull-cabinet up until 2016, showing the peculiar arrangement of the bird’s tongue bones.

Nancy and Ray Kendel discovered the remains of a Pileated Woodpecker near Smelt Bay, and it turned out that Nature had done a better preparation-job than any curator could hope for.

It can be quite rewarding to sort through the contents of an owl pellet and to try and reassemble the bits. (Is there anything a naturalist would rather do on a dark winter’s night ?)

So far, the analyses of owl pellets have not resulted in the discovery of any small animal species that weren’t already known to inhabit Cortes Island.

One group of mammals that might be expected to live among us, but that has not been reported at all so far, are the voles.

There are three species, almost literally “surrounding” Cortes Island:

- The Southern Red-backed Vole is known from Sonora and Hardwick Islands to the north.

- The Long-tailed Vole occupies the mainland shores around Bute and Toba Inlets in the east.

- Townsend’s Voles live on Quadra Island, immediately west of us.

(Cortes Island does have Muskrats, which can be included among the voles as North America’s largest species.)

Any documented observations of Voles on Cortes Island are of importance–ideally, sightings in the field would be accompanied by photographic evidence, but one could also hope to find a partial Vole skull with teeth preserved inside an owl pellet. The zig-zag edges of the three molars are diagnostic of the group.

It would be much appreciated if anybody coming upon any owl pellets on Cortes Island would drop the finds off at our local Museum. In return, the contributor may expect a short report, identifying the pellet’s contents, as well as a couple of photographs documenting the specimen.

2 Responses

I would like to show some of the figures of owl pellets – figs. 3, 11, 16 – as slides in a talk to the New Mexico Geological Society’s Spring Meeting in April of this year. Do i have your permission to use these photos in my Power Point slide show? My talk will be about my discovery of a regurgitite of a carnivorous dinosaur that is similar to the owl-pellet regurgitate in your photos. This dinosaur regurgitite is in rocks in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico that are ~65.8 million years old. Because birds are the living offspring of dinosaurs, my comparison of bones in owl pellets compared to regurgitated bones by a carnivorous dinosaur seems quite apt. I would be happy to send you a copy of my regurgitite discovery and my PP slides if you wish, but would ask that my regurgitite photo not be used by you until after i present my talk in April, and of course, I would want you to cite the photo from my talk as its source. To my knowledge, this discovery of mine is the first such well preserved dinosaur regurgitite ever found.

I am retired from the US Geological Survey and still working as an independent research geologist. I have published widely about the Paleocene dinosaurs of the San Juan Basin, NM – these dinos (including my regurgitite) survived the end-Cretaceous asteroid impact.

I hope I am not too late with the reply.

I will contact Christian Gronau, the person who took the photos. And we will get back to you. — Gina