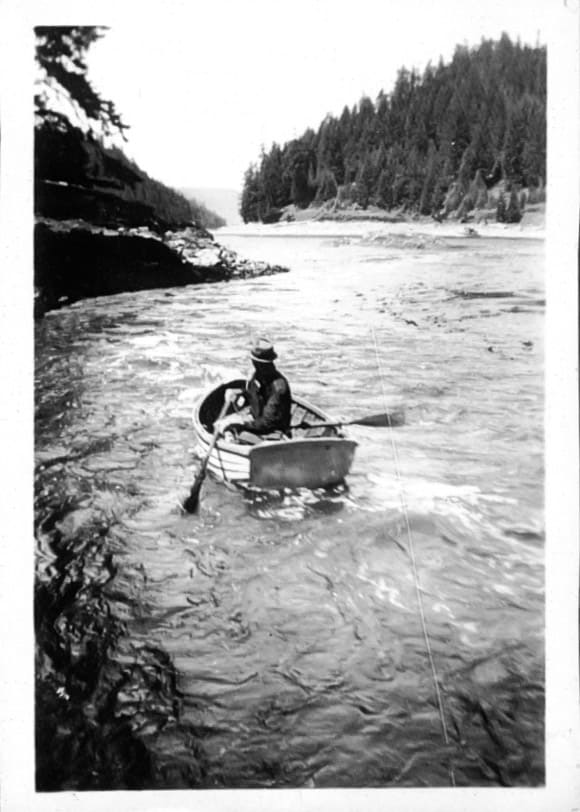

Like a number of families in the 1940s, the Herrewigs were a logging family living on their camp floats in Von Donop Creek (now called Von Donop Inlet) on the northwest of Cortes Island. Violet Herrewig and Amy McKenzie remember in 1949 when five blackfish (that’s what everyone on the coast called killer whales/orcas in those days) managed to follow some salmon into Von Donop Lagoon on a high tide. You can paddle a small boat into the lagoon when the tide is high, but on a low tide the water rushes out like rocky rapids in a river. Midge Calwell recalled she had “never heard of killer whales coming in there before that. We were flabbergasted when the men came home from logging and said the whales were there.”

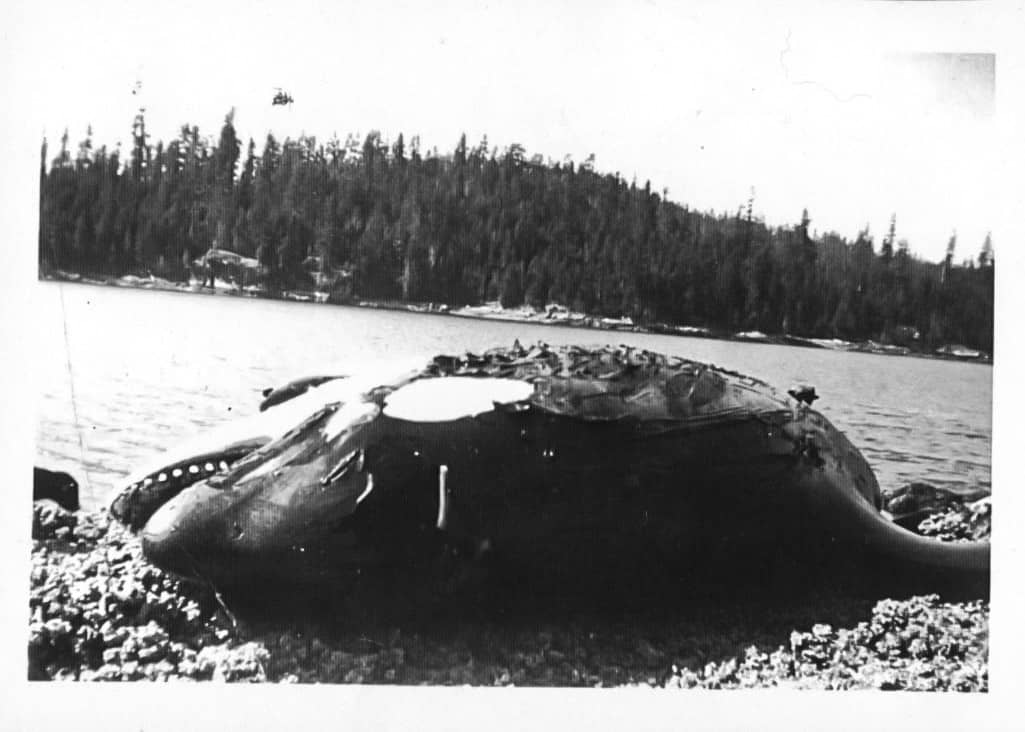

When the tide went out the orcas found themselves trapped, but even when high tide came in again, they still couldn’t find their way out of the lagoon and they just stayed there. The Von Donop Creek floating logging community took their dinghys into the lagoon, skirted around the edges to the far end, then on a high tide, tried to herd the trapped marine mammals out by banging on the sides of their rowboats and moving towards the exit channel. They repeated this on a number of high tides before finally giving up.

Midge also remembers many in the Von Donop logging float camps spent weeks sitting on the bank just on the outside waiting for them to come out. The small pod consisted of one large bull male, three females and one calf. The whales would come down to where the receding tidal waters flowed out of the lagoon and lay there, all in a line, and when the tide came in it brought fish for them to eat. Some boys watched them feed from up on a nearby spar tree used in logging operations. Schools of little fish swam in the shallows close to shore. The whales cruised back and forth in deeper water, then they’d turn, flap their tails, and wash the little fish into deeper water – lunchtime! One day Cliff, one of the boys high up on the spar tree, watched a baby orca being born. He could see clearly right down in the water from his perch. Two females kept bringing it up to the surface so it could breathe. They did that practically all afternoon but the newborn calf died.

Some scientists (not sure where from) who came to try and find out why they did not leave on a high tide, discovered the bull had received a deep wound in his side, suffered possibly while entering through the shallow, narrow, rocky entrance. Perhaps he didn’t want to take a chance of repeating this experience and so remained in the lagoon. This lagoon is fed by many streams and this dilutes the salt water flowing in with each high tide, which would not have been very healthy for the orcas over time. This saltwater dilution was also a factor in the death of Moby Doll, the first killer whale unexpectedly captured by the Vancouver Public Aquarium and kept outside False Creek in a temporary net pen at an old dock until her untimely death. Lesions form on their skin caused by parasites that don’t flourish in salty water.

Midge Calwell recalls the killer whales were in Von Donop Lagoon most of that summer in 1949. Word spread about the trapped whales, and people all over Cortes and nearby islands heard about the trapped orcas and boated around or walked across the island to see them. Some were fascinated and came to admire the whales. But there were those who didn’t care about them, and they walked in from Squirrel Cove with rifles for target practice at different times. They would shoot one, then return another time to shoot another.

The body of one female washed up on the beach just inside the lagoon. The other two females kept reaching out of the water and grabbing her tail, trying to drag her back into the water. The big male cruised back and forth behind where the females were apparently trying to rescue their dead friend. Their efforts had her tail fairly well chewed up before they gave up trying. Between the lack of food and all the shooting all five orcas died. The bodies beached in the lagoon. One carcass drifted out of the narrow entrance channel, the others remained to fertilize the lagoon beaches and provide meals for all levels of wildlife.

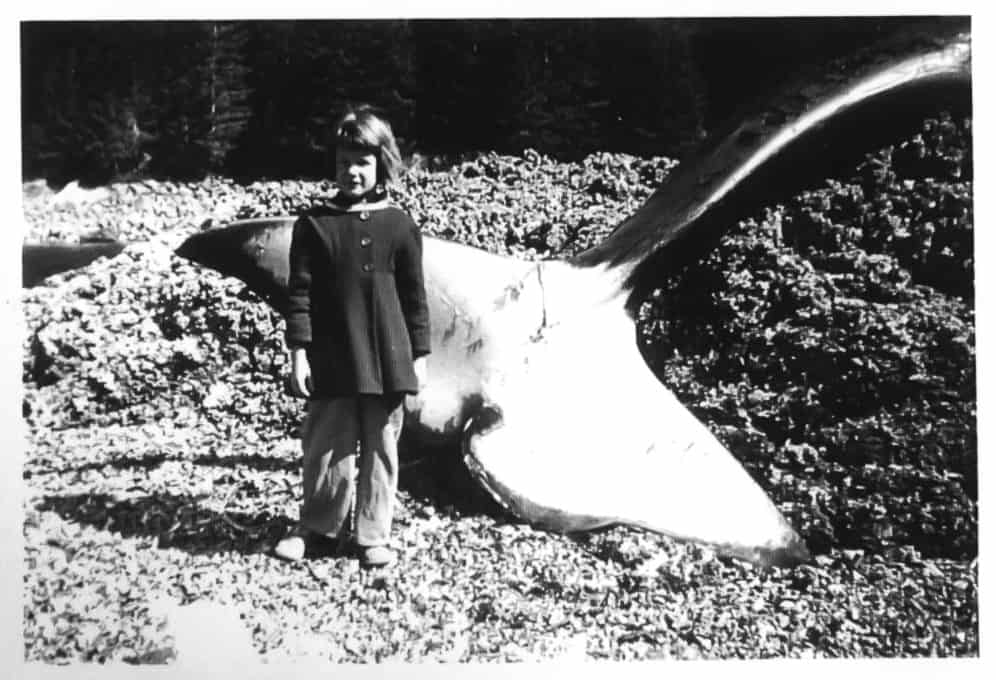

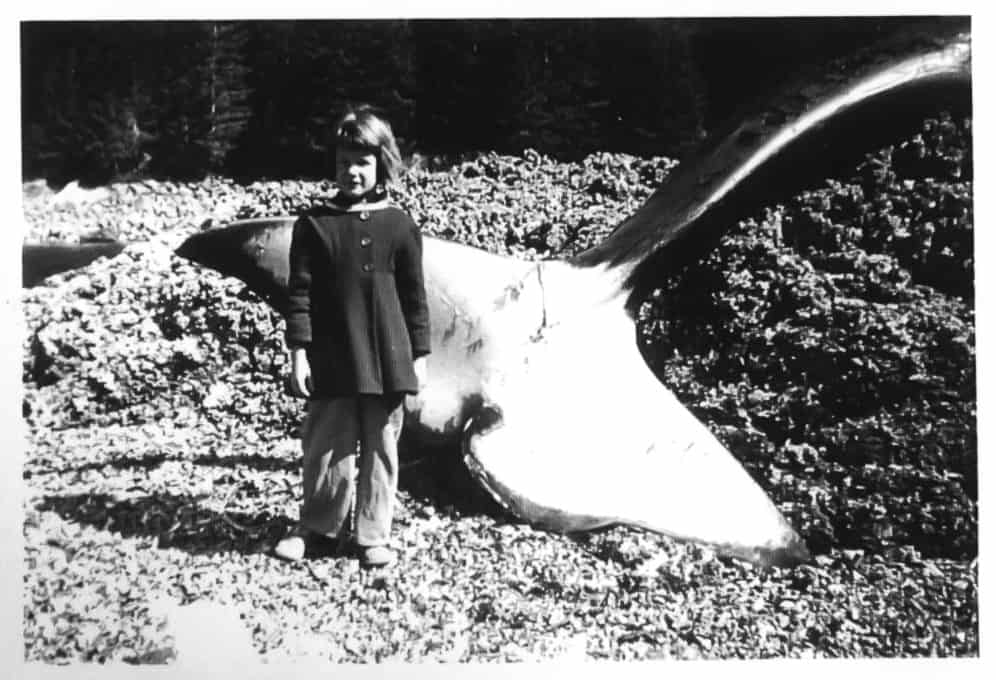

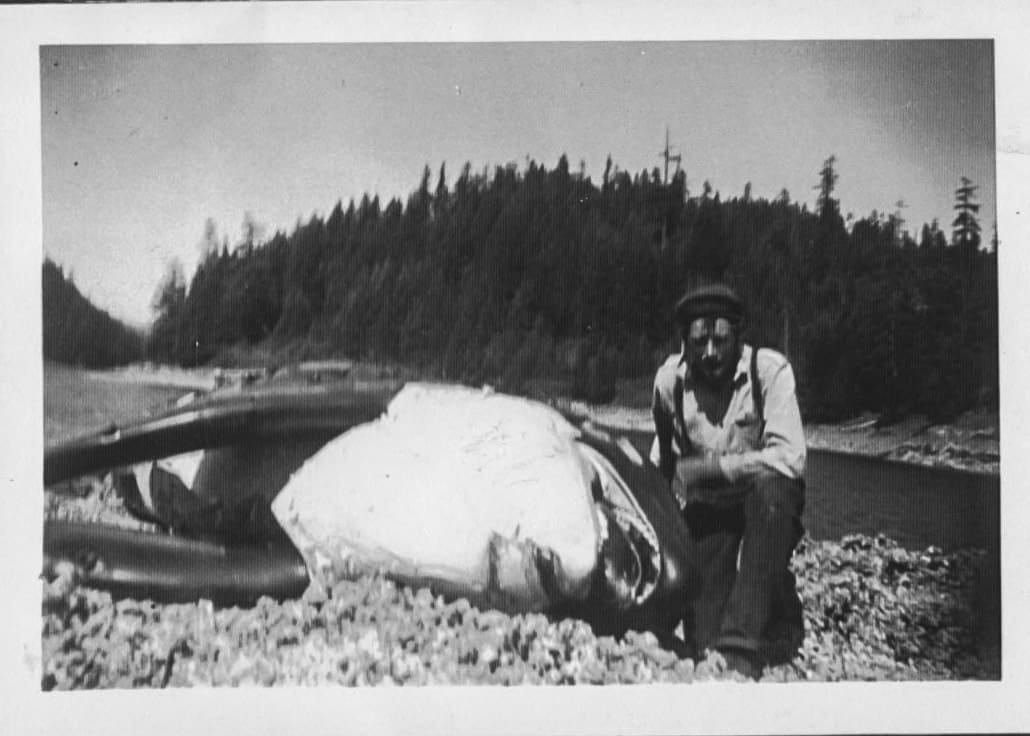

As a child, Doreen Guthrie recalls going into the lagoon to watch the killer whales and later to see the dead whales and have pictures taken with their carcasses, like others who lived in the Von Donop logging float camps. The carcass that eventually floated out of the lagoon, drifted down the inlet and lodged in the logs at the end of the Calwell’s float. Doreen said, “It stuck there, its skin all patchy and peeling and the gulls pecking at it. It didn’t smell too good, either! Not missing a chance for a practical joke, Dad got Archie (Doreen’s brother) down looking at its teeth – then he jumped on the carcass! Well, you know what a burp coming out of that rotting carcass would smell like! I think Archie threw up for a week!”

Wilf Freeman remembers visiting Von Donop sometime after the lagoon stranding incident when he met a dead killer whale drifting out at the mouth of the inlet. He contemplated taking a tooth out of its mouth because it was drifting there with its mouth agape and he thought the teeth would be loose because there was decay around them. But when he steered his boat close to the carcass, he really got a whiff of it and wasn’t eager to stay there, so he carried on into the inlet without acquiring a souvenir.

Mike Herrewig wrote to the Department of Fisheries but his letter was apparently ignored as there was never any response from them. They didn’t even come to have a look. After all the killer whales were dead, one carcass floated up across the way on Read Island and then Fisheries people arrived, cut it all up, and took pieces away. Too late. At that time Fisheries was supposed to be interested in protecting blackfish and in having a sanctuary for them where they wouldn’t be shot at. Back then fishermen thought the orcas were eating too many salmon and depleting the stocks and their livelihoods. So fishermen all along the BC coast were known to shoot them whenever they could.

Today orcas are more revered and protected. For centuries the First Nations People have carved them in totem poles and claimed them as their spirits. Until the 1960s when the Vancouver Public Aquarium had Skana, one of the first orcas on exhibit, most people did not give a darn or care for those whales living in the oceans of the world. With a few orcas exhibited in marine parks and aquariums, people could get close to them and see what amazing animals they are. This began the movement to save the wild whales. Most countries now protect and preserve all whale populations, with the exception of a few countries still conducting whaling fisheries.

In the 1860s the Gulf of Georgia had a number of whaling companies that completely fished out all the whales which then had the knowledge of the sheltered inside passage route to their Alaska feeding grounds, as they migrated north annually from California.

It has taken 150 years, but now many species of whales are again finding the inside passage and each year more and more of them are seen in our sheltered waters. For a number of summers now, humpbacks have been seen hanging around Cortes Island in the northern Salish Sea, along with some grey and minke whales, joining the local pods of orcas.

A more current story happened one day in mid-July 2017 when there were 5 humpbacks hanging around and breaching for a few hours, along with a pod of 7 orcas, just off Manson’s Landing on Cortes Island, much to the delight of the many pleasure boats anchored in Manson’s Bay. The pod of orcas even came into the inner bay, passing under some boats and right next to the government dock.

In mid-August 2017, one afternoon there were 3 humpbacks breaching repeatedly on the very edge of Whaletown Bay on Cortes Island where the ferry comes in from Quadra Island. Word quickly spread from the vehicles waiting in line at the bottom of the hill all the way back up the lineup of about 40 vehicles. Everyone got out of their cars and came running down the hill to watch the amazing spectacle so close to shore. Eventually, the arriving ferry had to slow down & swerve to enter the bay. Once the ferry was loaded and on its way again, we heard the usual safety announcements and then the captain came over the speakers with, “Welcome aboard the Cortes to Quadra whale watching cruise!” Humpbacks and orcas are seen many times on this ferry route.

Sources:

From the Cortes Island Museum’s Von Donop Album interviews and stories by:

— Mike, Violet & Amy Herrewig

— Midge Calwell

— Doreen Guthrie

— Wilf Freeman

And from:

— The Daily Colonist September 28, 1969, “A Holiday With the ‘Hermit’ of Von Donop Channel” by Irene Hawkin-Orr.