Most readers probably had enough of these ramblings on Wasps by now. The problem with any area of inquiry into this prodigiously fecund world of ours is that the closer you look, the more there is to see. Completeness is not achievable, and limits have to be imposed artificially: this shall be the last instalment of this short three-part walk with Wasps…

So, the following is nothing more than a picture gallery, offering a mere suggestion of the huge diversity of Hymenopteran forms and lifestyles. The gallery is organized in almost as random a fashion as we might expect to encounter the various members of this group of insects during our daily meanderings – whenever we manage to lift our eyes from our own myopic human-all-too-human and narrowly sign-posted path.

All photographs were taken on Cortes Island.

Where is Alfred Kinsey when you need him? And why did he ever abandon the study of parasitic (especially gall-forming) Wasps for that other topic?

Among the million or so specimens he personally collected in his earlier entomological career, the Wasp pictured in Fig. 1 surely was represented. Quite a few Torymidae are hyperparasitic by usurping the galls produced by other Wasps, which are themselves parasitic on various plants.

Alfred would know what species this is (maybe he even named it himself) but he is not telling.

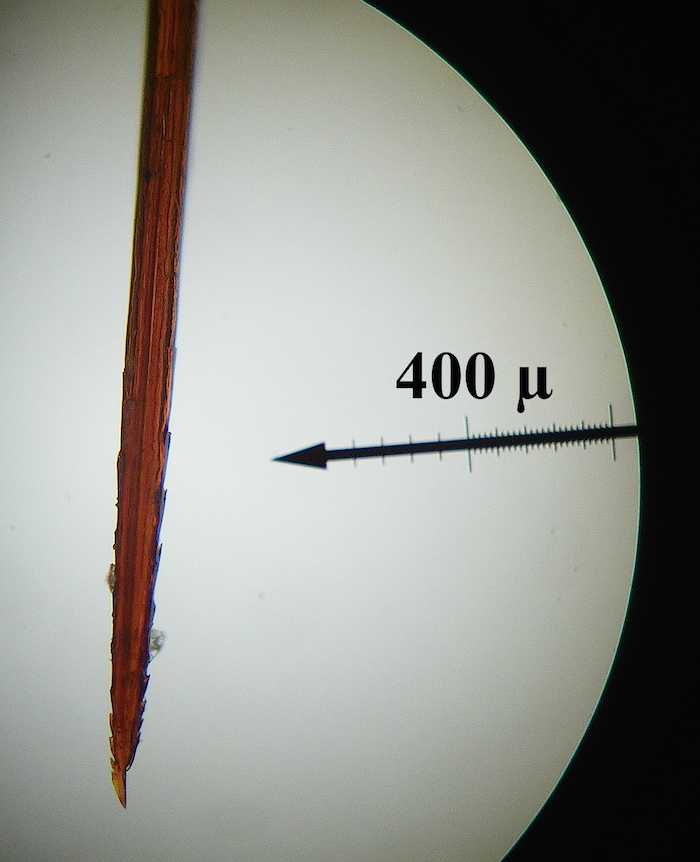

The ovipositor, that long terminal appendage, is used to insert eggs deep into the tissue of plant or animal hosts. It is a conspicuous feature of parasitic Wasps.

No group has developed this more dramatically than the Ichneumonidae:

Sometimes called “Stump Stabbers”, these wasps hunt for the grubs of wood-boring insects and insert their ovipositor an inch or more to reach a victim, the presence of which can be sensed by tapping antennae and feeling vibrations with the legs ! The egg is laid inside the body of, say the larva of a Buprestid Beetle (known as Flat-headed Borers), where it will hatch and eat and grow, being careful not to consume any vital organs until the very end.

Charles Darwin had profound thoughts about these wasps (letter to Asa Gray, 1860):

“But I own that I cannot see, as plainly as others do, & as I should wish to do, evidence of design & beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent & omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidæ with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.”

Another group of Wasps, the Specidae, would have inspired Darwin to similar thoughts:

Here (Fig. 3), Sphex procerus, also known as Thread-waisted Wasp or, sometimes, Digger Wasp, is dragging the paralyzed body of a Pine White butterfly caterpillar (Neophasia menapia) into the hole she has dug, to bury it alive and lay one egg on it, for her offspring to hatch and feed on.

Incidentally, this is the genus eponymous for Spheksophobia: the fear of wasps – though, in the case of the caterpillar, there is nothing irrational about that fear …

Of course, all these Wasps with their seemingly cruel feeding habits serve a “good” cause: they are important natural controls of forest and garden pests. (As a gardener, think Cabbage White, in place of Pine White.)

It is obvious, though: the natural world does not cater to human sensibilities.

The, perhaps more familiar, Mud Daubers also belong in this family, the Sphecidae.

Here (Fig. 4), a trio of the Black and Yellow Mud Daubers (Sceliphron caementarium) are engaged in a ritual, the meaning of which is best known to themselves.

Their small igloo-like mud nests are quite common in well protected areas under eaves and inside garden sheds. The one in the following picture (Fig. 5) separated from its attachment surface and shows the larval chambers inside.

The Blue Mud Dauber (Chalybion californcium) is occasionally glimpsed as a steel-blue glint flitting through the sunlight (Fig. 6).

[divider]

The picnic area at Mansons Lagoon was favoured by these large beautiful wasps [Fig. 7] this summer (2015), where one could observe dozens of these, nonetheless solitary, wasps go about their business of excavation. Watching them closely, it is surprising how much their efforts resemble the digging of dogs : vigorous sprays of sand are ejected backwards by the strong actions of the forelimbs.

The eggs laid in these sandy caverns are provided with various insects, usually flies. Sand Wasps have an uncanny sense of location : after flying off in search of prey, they unerringly return to the correct hole in the ground. Behavioural studies have been conducted, trying to determine how these wasps orient themselves in the landscape. Certain geographical landmarks, like prominent rocks or branches on the ground, were moved, and that caused the Wasps considerable confusion. Some Sand Wasps have the habit of hovering uncomfortably close to human beings : this is not a sign of aggression and certainly not of personal interest : they are looking for flies, which, typically, accompany large mammals and, in turn, are looking for edible evidence of sloppy eating habits and general uncleanliness.

[divider]

To end this rambling account on a familiar note, a look at the common, but nonetheless deeply mysterious distant cousin of the Wasps, the Honey Bee.

As summer progresses and many flowers have come and gone, Mint plants become highly prized food sources for Apis mellifera. Being of major interest to humans, this Hymenopteran has been studied in enormous detail, and nothing needs to be added here. Two anatomical details are clearly visible in the photograph above and bear pointing out :

The long labium or tongue can be seen probing a flower.

The flattened and enlarged parts of the hindlegs (tibia and basitarsus) are rich in bristles (setae) and are supremely suited for packing and carrying pollen from flowers to hive.

As a poignant finale to this summer’s observations, the author finally was stung – not by any of the feared and supposedly aggressive species, but by the cuddly and generally well loved Honey Bee ! To prove a point, made in an earlier chapter of this blog, the stinger got stuck in the skin, and the entire stinging apparatus was ripped out of the Bee’s abdomen: a fatal injury for the insect.

[divider]

It might be easier for the reader to abandon the theme of Bees and Wasps than it is for the author. Once begun, any investigation into any aspect of our world (however profound or nerdy it might appear) takes on a momentum of its own, and one quickly discovers that there are no boring topics, only areas of ignorance – which, once looked at even casually, reveal underlying patterns of deeply satisfying beauty.

If one or two readers have their eyes opened to this simple fact, then writing the three brief essays for the Museum Blog has been well worth the effort.