Text and photographs are by Christian Gronau unless indicated otherwise.

This story reminded me of a story and then another:

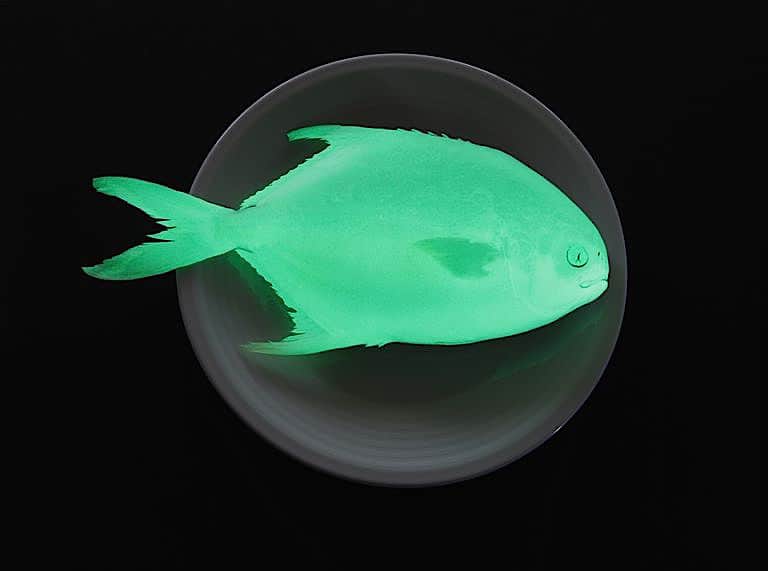

A friend, after walking his dog at night on a Cortes Island beach, reported how some old and smelly fish remains, being pawed by his excited companion, glowed in a pale bluish-green light. He had (re-)discovered rotting fish as a light source! (Fig.1)

Hard to imagine nowadays, but early miners had a serious problem taking lamps underground. Especially coal mines were prone to build up dangerous levels of combustible gases (so-called “firedamp gases”), mainly methane. Until the invention of safety lamps, which attempted, with some degree of success, to isolate an open oil flame from the surrounding air and its potential firedamp content, the alternatives were few: work in the dark or risk being blown up in an explosion of gas and coal dust. There was one further option: carry a bucket of rotting fish with you! The faintest of lights and a lot of stink! Better than nothing?

Why certain bacteria emit light while being busy with the serious work of rotting and recycling dead meat seems like a tricky question. A mere coincidence of chemistry, perhaps?

http://nevertoocurious.com/2014/08/28/bioluminescence/

There are other methods.

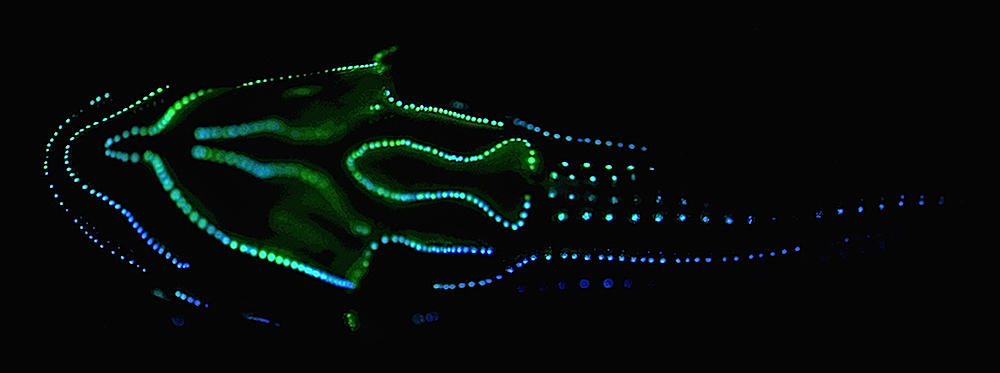

Other than dying and decomposing, there are other ways to harness the bioluminescent abilities of certain bacteria. Some fish live happily in a symbiotic relationship with their microbial tenants, arranging rows of “houses” (called photophores) on their bodies in patterns that serve a number of purposes, from luring prey-fish or mating partners to confusing attacking predators.

One fish species, famous for its bioluminescent light-show, is the locally well-known Plainfin Midshipman (Porichthys notatus). Turn over a few small boulders in the lower tide zone and, in spring or summer, chances are you will uncover a pugnacious fish, up to one foot long, staring you down with his toothy mouth agape. (Fig.2 & 3) This will be a male Midshipman, guarding eggs that he has fertilized. He being a so-called Type I male, building “nests,” singing to the females (more of which below) and guarding the eggs he thinks of as kin – which is all in good order, unless a Type II male has been lurking around: this ballsy type is of smaller size, but has enlarged testes. He sometimes pretends to be a female, or he just hangs around the nest of the regular family-type male. When a female enters the nest and lays her eggs, Type II will use his superior testicular power to blast his sperm through the cracks between the rocks that form the nest shelter – and: voila!

And invariably, the underside of the rock you moved to uncover this scene has eggs attached to its underside. (Fig.4 & 5)

And make no mistake: the male is guarding those eggs! His pointy teeth are very capable, and they will draw blood. (Fig.6)

Some males – the lucky ones – get to fertilize and guard the eggs of several females. The downside of such prolific genetic success is that occasionally one male has to remain on guard for several months (the record is 131 days!), even though a single batch of eggs takes only around 40 days to hatch. In such extreme cases, the male Midshipman may lose almost one-quarter of his body weight. In other words: the dedicated father nearly starves to death. He may be forgiven, one is inclined to concede, if he once in a while takes a little nibble and cannibalizes some of his own kids …

Back to bioluminescence.

The Plainfin Midshipman has beautifully arranged rows of photophores on its underside and is capable of creating eerie and enchanting light-shows (Fig.7 & 8).

Except in our local waters it does not!

While having a fully functioning apparatus for producing bioluminescence, our local fish are lacking the fuel to power the process: luciferin. A dietary deficiency seems to blame: in their northern range the Midshipman fish lack access to a specific kind of Ostracod (prob. Vargula tsujii), a tiny bivalved crustacean, part of the oceans’ mesoplankton, which is itself bioluminescent and, upon becoming food for the fish, surrenders its bacteria, which find their way to the photophores conveniently provided by their ingestors. This happy coincidence applies only to the southern populations of Porichthys notatus! Dietary dependency for the presence of photosynthesis is a clear and logical explanation – but, as is so often the case in evolved natural systems, the closer one looks the more complicated everything gets, or so the literature tells us. E.g.: E. M. Thompson et al. Marine Biology 98, 7-13 (1988) “Latitudinal trends in size-dependence of bioluminescence in the midshipman fish Porichthys notatus.”

And there is another strange story to be told about the Plainfin Midshipman:

“It sounds like the drone of a guitar amplifier, but it’s actually the amorous serenade of a fish called the plainfin midshipman. During the summer, this sonorous sea creature hums to attract females to its rocky seafloor love nest.

‘It sounds like a drone of bees or maybe even the chanting of monks,’ neurobiologist Andrew Bass, who has studied these fish extensively, told LiveScience.

The hum is so loud that for years, houseboat owners in Sausalito, Calif., complained it was disrupting their sleep and drowning out conversations. Theories circulated about what was making the strange noise — sewage pumps? Military experiments? Submarines? Ultimately, scientists discovered that the plainfin midshipman (Porichthys notatus) was causing all the buzz.”

https://www.livescience.com/27237-fish-sings-for-mates.html

It turns out that the hulls of houseboats make perfect resonance chambers to amplify the midshipman’s love songs …

And one more story:

A few local naturalists have reported hearing that mysterious hum, in the right place and at the right time. Perhaps on Cortes Island’s Sutil Reef, at a lowering tide, in May and maybe in June.

Late spring and early summer are the seasons when both sexes of the Plainfin Midshipman seek out shallow waters to mate, lay their eggs and rear their young (the latter part of the job being carried out by the male of the species exclusively). And they do so in very large numbers indeed. This recurring abundance has not gone unnoticed by fish-eating predators, most notably bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). The raptors congregate at choice beaches, and for a while, their diet consists almost exclusively of Plainfin Midshipman fish. (Fig.9), In some locations, a hundred eagles might assemble for the feast, with each individual catching a dozen fish or more per day. Spread out over a couple of months, this adds up to a lot of fish: an indication of the immense numbers of Plainfin Midshipman fish populating our waters.

Not all that much to look at, this plain little fish has plenty of stories to tell and is well deserving of our admiration and protection. Remember: whenever you are overturning boulders in the intertidal zone, do it gently and always return them carefully to their original position. Many living things depend on that, and they will thank you.