Childhood memories are some of the best. As a young boy, I spent my summers on Cortes. It was before the days of ferries and power. We stayed in our little shack on the beach, and when the evening darkness came, I would ask my father to tell me stories of the olden days.

My father Nicol was born in 1906, the youngest son of pioneer John Manson, a teacher by profession, and perhaps that accounted for his wonderful storytelling of pioneer life. I can’t claim to recall much of the story told that night, but I mostly remember the look on my father’s face as he spoke of the hard-working Nakatsui, the Japanese horse logger who had homesteaded down the beach from us. I knew that look well. It was one of respect. The same look I saw when my father talked of his own father’s exploits.

As long as I can remember, it was called the Jap Ranch. To me, it seemed a term of endearment, especially coming from the mouth of my father. Today it is frowned upon to refer to Nakatsui’s ranch by its old name. The name was not derogatory in its day, no more so than referring to a British person as a Brit. However, all that changed in 1941 with the outbreak of war in the Pacific. Henceforth the term would become offensive, an enigma for me and my memory of the abandoned farm with the intriguing name.

I never knew Nakatsui; I was born four years after he died. When I started this story, I didn’t know if Nakatsui was his first or last name; it was just a vague memory of my father talking about Nakatsui.

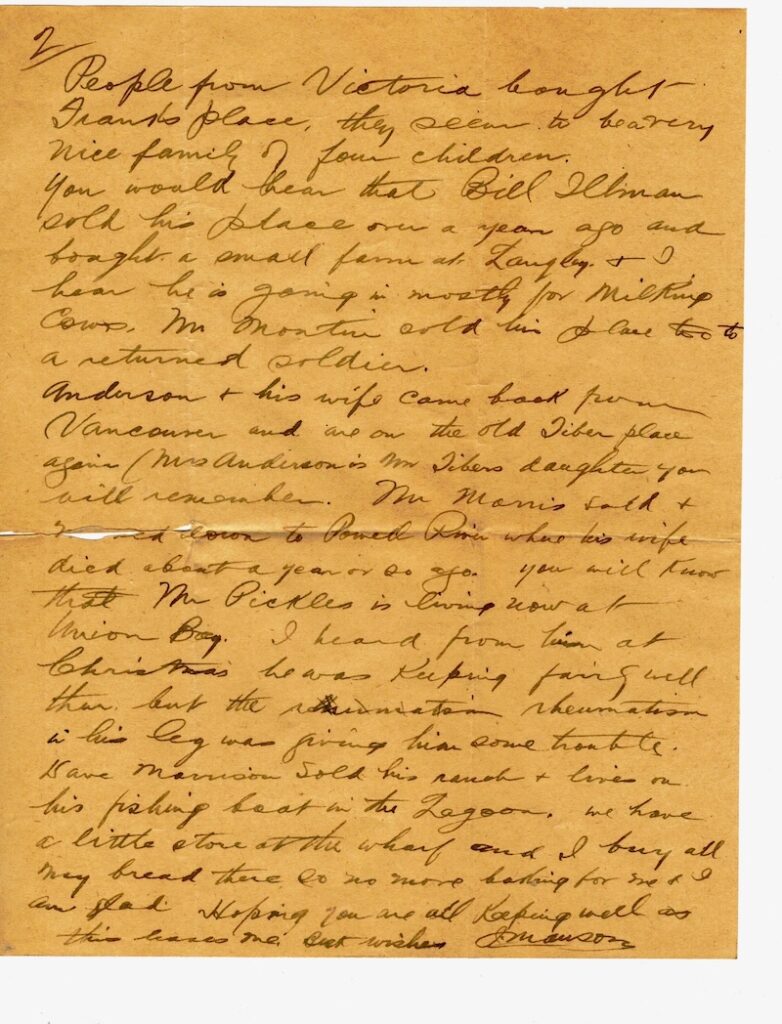

Yaichi Nakatsui was born in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan, in 1881[1]. At the age of 19, he came to Canada, settling on Cortes Island, where he went to work with a group of Japanese horse loggers.

Yamaguchi Prefecture was known for its agriculture, and it is no surprise that Nakatsui kept an eye out for land to farm. We don’t know where Nakatsui lived upon his arrival on Cortes in 1900, but he listed Mansons Landing as his place of residence[2]. In 1912, Yaichi Nakatsui married Sayo Kawamoto, age 22[3]. A year later, their son Kazuo was born. Bruce Ellingsen recalls his mother May saying she went to school with Kazuo here on Cortes. On March 19, 1924, at the age of 10, Kazuo passed away from tuberculosis[4].

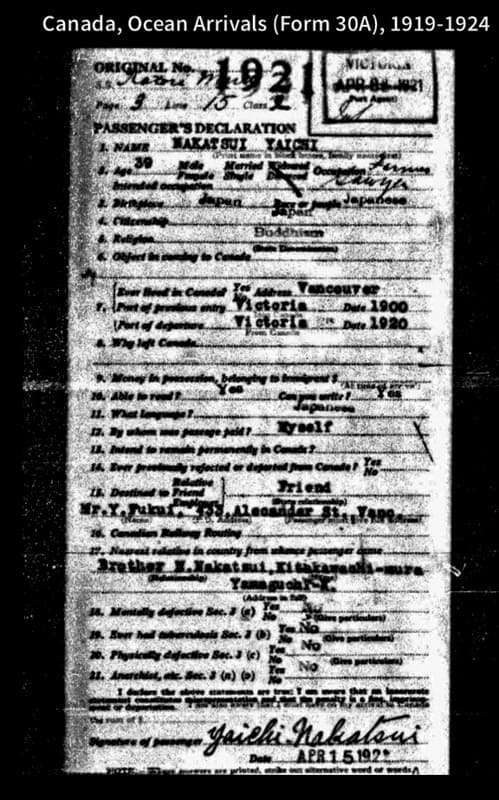

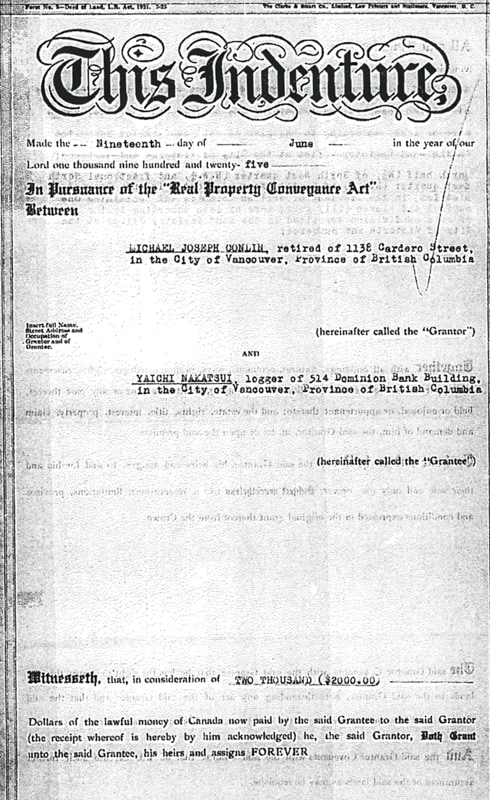

In 1925, Nakatsui purchased the site that would become known as the Jap Ranch, 111 acres for $2,000 from Michael Conlin[5]. Conlin wasn’t the first to homestead here. Jacob Grauer had pre-empted the land in 1891 and purchased the land the following year for a dollar an acre[6]. Grauer sold to Conlin in 1913 for $1,500[7]. It is possible that Nakatsui may have rented here prior to buying.

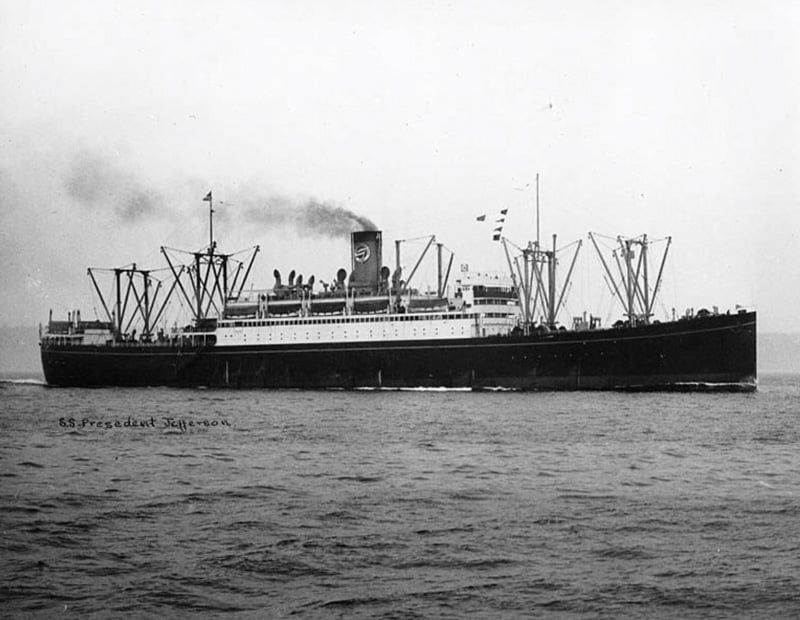

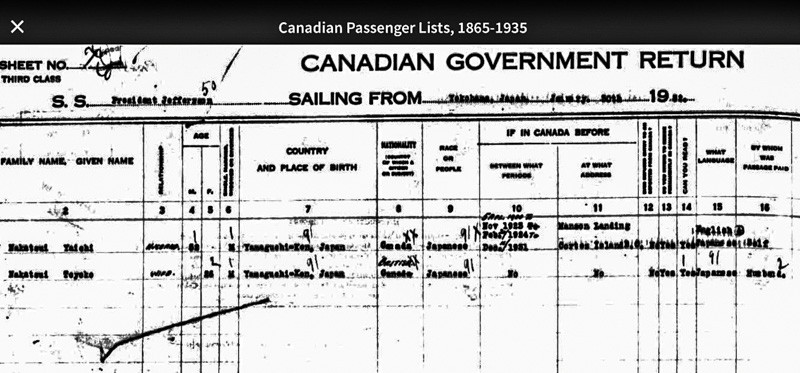

Within four years of buying the farm, Sayo would be dead[8]. Nakatsui would remarry. On 30 January 1932, he departed from Yokohama aboard the SS President Jefferson with his wife Toyoko, arriving in Victoria eleven days later[9]. Before long, they were back on Cortes farming.

At first, it looked like the Nakatsuis might be spared. Order-In-Council P.C. 365, issued on January 16, 1942, called for the removal of all male Japanese nationals between the ages of 18 and 45. Nakatsui was 61. But three weeks later, US President Roosevelt signed an order calling for the removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the American coastline. On February 24, Canada followed up with Order-In-Council P.C. 1486, which called for the removal of all persons of Japanese origin. Nakatsui and Toyoko were sent to the Interior and were part of more than 21,000[12] people removed from the coast without charge or trial.

Ten years later, Nakatsui would be dead, having taken his own life while confined to the Provincial Mental Hospital at Essondale[13]. Officially diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia, perhaps brought on by too many painful losses that he could not recover from, he was now at rest.

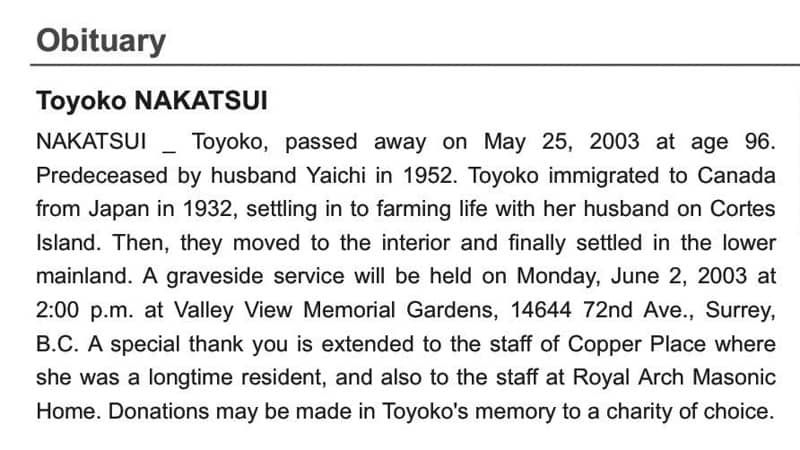

Toyoko would live for many years, dying in 2003 at the age of 96.

In between the hard-luck episodes of Nakatsui’s life, there are some good stories about his character and happier times. Andy Ellingsen recalls his grandfather, George Freeman, speaking in glowing terms of the hard-working Nakatsui and his horse logging. And May Ellingsen recorded the following: “Nakatsui once showed Nick Manson a great row of sake bottles saying “seven men – two days.” Nakatsui gave up his drinking when he started his farm in 1925.”[14]

And then an enigma, from May’s writings, “All Japanese loggers were (maybe unthinkingly) very hard on their animals, especially horses which they would load heavily, whip liberally and pay no heed to lameness or ailments. Nakatsui was reported and arrested then taken to Powell River jail on account of his horse having raw shoulders when he hauled heavy loads without a proper collar. He was arrested more than once for animal cruelty and taken to jail.”[15]

Nakatsui had a sense of humour. Again, from May’s notes, “At one time, he decided to try hanging lanterns in his orchard to discourage raccoons. He had no success and told John Manson that “those gawdam coons just got more light to feed by!” And Nakatsui once told Mrs. Petznick that he had no relatives, only “two tomato cans in church” – a reference to ashes of relatives in a canister in a Japanese church.”[16]

Nakatsui helped build the St. James Church at Mansons Landing. From the plaque displayed at the Cortes Museum we know it was 1927 when Mr. Nakatsui cleared the land that Mr. Froud had donated for the site. Ten years later, to commemorate the coronation of King George VI of Great Britain, an English Oak was planted on the church grounds, and Nakatsui donated a Canadian Maple and suggested that it would be appropriate for the two to be planted side by side both trees of which are still standing today.

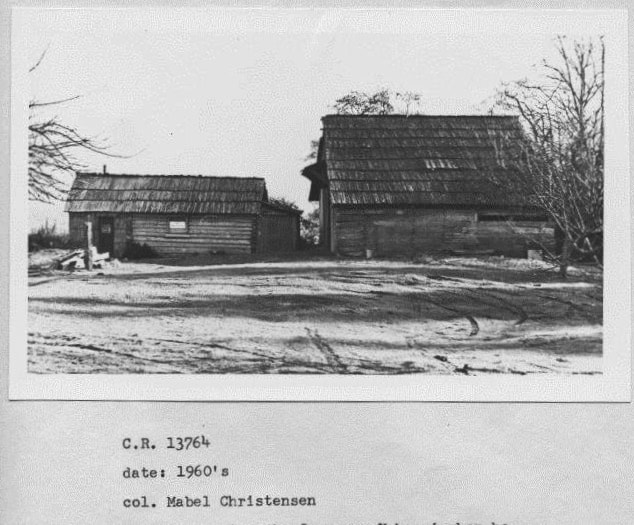

June Cameron, author of Destination Cortez, writes of her visit as a child to Nakatsui’s farm after Yaichi and Toyoko were gone and tells of how impressed she was with the neatness and beauty of the surroundings. She recalls the well-pruned fruit trees, a lovely grape arbour, and the outhouse, a communal affair where people could sit side by side, a concept that she was not aware existed in the world.[17]

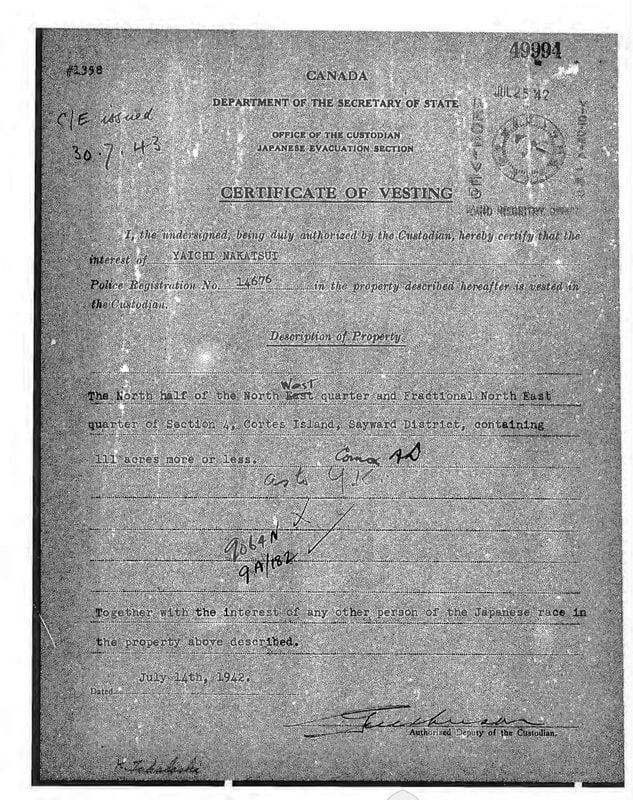

In the months before 7 December 1941, all Japanese Canadian males were ordered to register with the RCMP. Note the Police Registration Number on the certificate above. It is ironic that the only existing picture of Yaichi Nakatsui might be the photo on the Police Registration card.

Historians call the internment of the Japanese Canadians a dark hour in Canada’s history. The series of Order-in-Councils passed under the War Measures Act leaves no doubt.

On June 29, 1942, Order-in-Council P.C. 5523 authorized The Director of Soldier Settlement to purchase or lease farms owned by Japanese Canadians. He subsequently buys 572 farms without consulting the owners.

On January 23, 1943, Order-in-Council P.C. 469 granted the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property the right to dispose of Japanese Canadian properties in his care without the owner’s consent.

The proceeds were used to pay auctioneers and realtors and to cover storage and handling fees. The remainder paid for the small allowances given to those in internment camps. Unlike prisoners of war of enemy nations who were protected by the Geneva Convention, Japanese Canadians were forced to pay for their own internment[18].

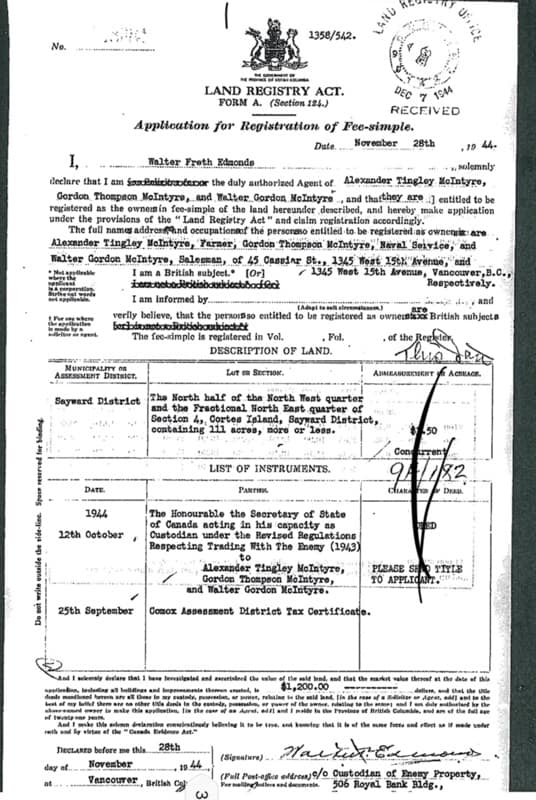

On November 28, 1944, the Honourable the Secretary of State of Canada, acting in his capacity as Custodian under the Revised Regulations Respecting Trading With the Enemy (1943), finalizes a transfer and sale of Nakatsui’s farm to three brothers (McIntyre), one of whom lists his occupation as Naval Service[19].

The land was sold to the McIntyre’s for $1,200. Nakatsui paid $2,000 nineteen years earlier.

As part of the Soldier Settlement Plan and the Veterans Land Act (1942), it would appear that the sale was to provide a farm for one of Canada’s war veterans. It is another irony – sell one immigrant’s land to provide land for another immigrant.

I am saddened by my findings as I tried to unravel the mystery of the man called Nakatsui. I realize I am the same age as Nakatsui was when he and Toyoko were forced to leave their Cortes home in 1942. It feels as though I have a bond with him. We have both felt the warmth of the returning spring sun and the sting of the southeast-driven rain. We have heard the songbirds sing, the north westerlies blow in the treetops and we have heard the crash of the waves upon the beach. We have looked at the mountains of Desolation Sound and Vancouver Island and the low-lying islands of Long Tom and Mitlenatch. We have smelled the manure in our barns and the sweet scent of garden flowers. We have squinted into the sunshine of the low-lying winter sun and covered our heads from the August sun. We have walked the same beaches and swum on the same tides.

I can think of much we have in common, but unlike Nakatsui, my heart has been spared the ache.

It is difficult to judge the decisions of the government of the day. There may have been a better way to deal with the concern over the Japanese Canadians living on the BC Coast.

Today Nakasui’s farm is being well cared for. It has been divided into three properties which are known locally as the Loon Ranch, Treedom and the Saltwater Farm.

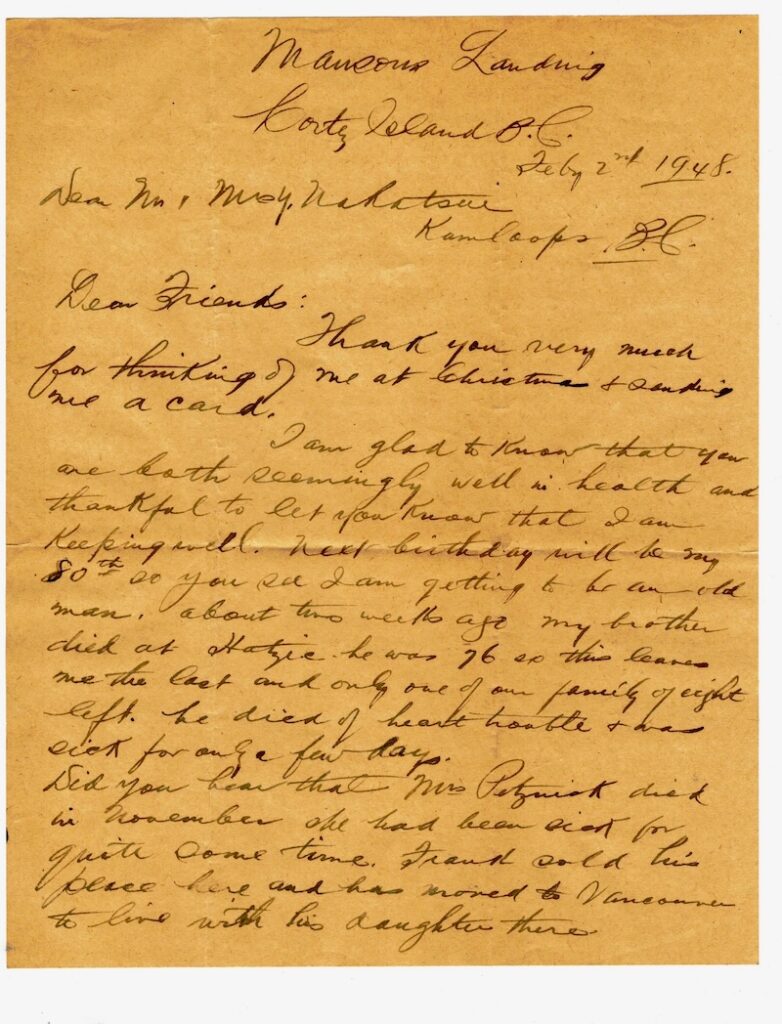

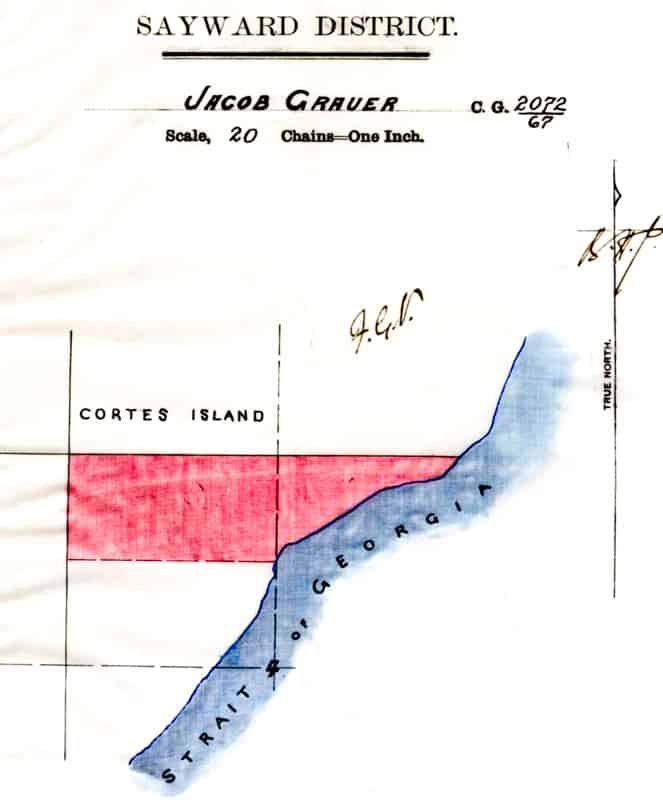

In February 2024, Mike Manson found his grandfather’s letter written to Nakatsui in 1948. Their internment would have been over by then. Mike’s grandfather is replying to a letter they had sent him, but sadly, his letter was returned, and they would not have read this newsy letter mentioning a number of the pioneer families.

Acknowledgements

- Judi Pidcock for her help with research at Ancestry.com

- Jeff Beddoes, BCLS, CLS, Senior Deputy Surveyor General, Land Title and Survey Authority of BC, and his staff for their invaluable assistance in tracing the land dealings.

- Cortes Island Museum and Archives Society

Updates

- Originally published on 6 December 2017

- Some updates in July 2021

- Addition of Mike Manson’s grandfather’s letter on 29 February 2024

Sources

[1] BC Archives – Marriage Certificate, Reg. No. 1912-09-023697

[2] Ancestry.com – Passenger List

[3] BC Archives – Marriage Certificate, Reg. No. 1912-09-023697

[4] BC Archives – Death Certificate, Reg. No. 1924-09-338176

[5] LTSA – conveyance 9664N

[6] LTSA – Crown Grant 2072/67

[7] LTSA – conveyance 10513-I

[8] BC Archives – Death Certificate, Reg. No. 1929-09-418758

[9] Ancestry.com – Passenger List

[10] CIMAS – photo in Campbell River Museum, Mabel Christensen collection

[11] Order in Council P.C. 365

[12] japanesecanadianhistory.net

[13] BC Archives Death Certificate, Reg. No. 1952-09-011418

[14] CIMAS – records from May Ellingsen

[15] CIMAS – records from May Ellingsen

[16] CIMAS – records from May Ellingsen

[17] Destination Cortez, pages 199,200

[18] japanesecanadianhistory.net

[19] LTSA – conveyance 148084-I